Eddie-Baby

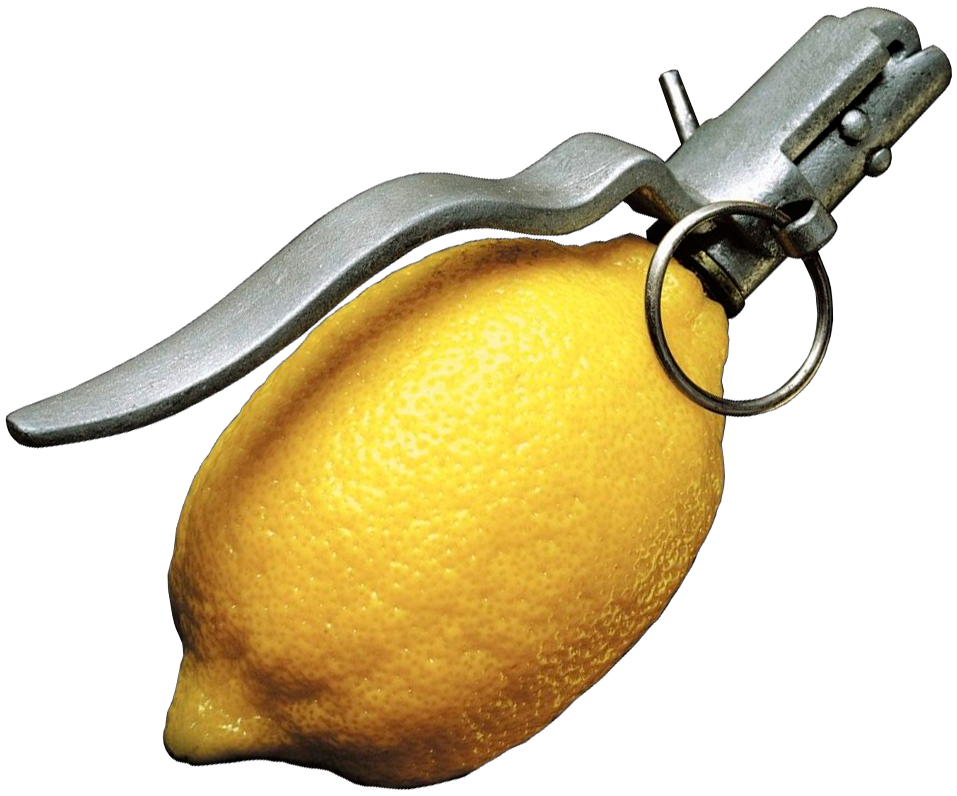

Eddie Limonov

It was at the age of eleven that Eddie-baby’s life changed abruptly. That was the day after his fight with Yurka. Yurka was a year older than Eddie-baby, and had the pink, healthy cheeks and the strong healthy torso of a boy born in the Siberian town of Krasnoyarsk. In Eddie-baby’s opinion, Yurka was an absolute fool. Eddie, however—eleven years old and still inexperienced—did not yet realize that a fool can be as strong as a young bullock. Strong and dangerous.

The fuss was about nothing. Eddie-baby had drawn an absolutely inoffensive caricature of Yurka, which showed him asleep during a lesson. This healthy boy, in fact, was always inclined to doze off in the hot classroom. When Eddie-baby and another artist, Vitka Proutorov, pinned up the wall-newspaper, Yurka elbowed his way through to Eddie and said that he wanted to «have a knock» with him. «Let’s have a knock, Savekha,» he said. «Savekha» was a derivative of Savenko, Eddie's surname. Among the pupils of No. 8 Middle School it was fashionable to call each other by a name that ended in «kha». Sitenko was called Sitekha; Karpenko, Karpekha; and so on.

Yurka the Siberian beat up Eddie-baby until he was unconscious. And he abruptly changed Eddie's life, just as the appearance of the Archangel Gabriel changed the life of Mahomet and made him a prophet, and the falling apple made Newton Newton.

When Eddie-baby came to his senses, he was lying on the floor in the classroom; around him stood several of his classmates with frightened faces, while a little further away Yurka was sitting calmly at one of the desks.

«Well, did you get it?» said Yurka, when he saw that Eddie-baby had opened his eyes.

«I got it,» Eddie-baby agreed. Whatever else he may have lacked, he had a firm grasp of objective reality. Together with his sympathizers he made his way to the toilet, where with water they cleaned off the chalk and dust that had stuck to his trousers and his black velveteen jacket. Five-kopek pieces, amiably proffered by his classmates, were applied to Eddie-baby’s bruises, his whole physiognomy being adorned with bruises and scratches. The incident was closed.

*

Going home after school that day, Eddie-baby analysed his life, all eleven years of it, examining it from various points of view. Only at home was he slightly distracted from this process by his mother's frightened cries and by the business of parrying her questions: «Who?» «Where?» «When?»

All that Eddie-baby said was that he had been in a fight. He did not say who had beaten him, rightly considering this to be his own affair. In Eddie-baby’s opinion, questions such as «Where?» and «When?» were pointless.

That day he did not touch his French kings or his Roman emperors, did not look at any of his notes nor surround himself with books. He lay on the divan, his face turned to its upholstered back, and thought. He heard his father come home, and even stood up obediently so that his father might inspect his bruised and scratched physiognomy, but almost at once lay down again in the same position, nose to the wall. When his father and mother began to bore him a great deal droning away behind his back, he pulled one of the divan cushions from under his head and covered his head with it. His father used to do this whenever he lay down for a nap after Sunday lunch. Eddie-baby, however, was not sleeping; he was thinking.

To this day Eddie-baby clearly remembers the next morning down to the slightest detail—the bright spring sunshine, and how he walked along the path behind the house, his usual route, in order to come out on First Transverse Street, which should have led him straight to school. On that day, however, Eddie-baby stopped for a short while behind the house, under Vladka and Lenka Shepelsky's windows, put his haversack on the ground, untied and took off his Pioneer's kerchief and stuffed it into his pocket. This gesture was unconnected with any renunciation of the Pioneer organization; by taking off his kerchief Eddie-baby was rather symbolizing the start of his new life. Eddie-baby had decided to abandon his books, to enter the real world, and in the real world to become the strongest and the boldest.

He decided to become a different person and became one that same day. Usually taciturn and self-absorbed, on that day Eddie bombarded the teachers with witticisms and cheeky, caustic remarks, for which the French mistress, shaken, sent him out of the classroom. He spent the rest of the lesson hanging about in the corridor, along with a tough second-year boy called Prikhodko, catching flies basking in the first spring sunshine as they sat on the window-ledge. Then, together with Prikhodko, he committed his first sexual crime: they invaded the female toilet on the fourth floor, where several girls from class 5A were hiding to escape from a PE class, and there they «squeezed» them. Eddie-baby had seen other schoolboys do this before, but he himself had never felt any desire to commit an act of «squeezing».

In the raid on the girls» toilet, he imitated Prikhodko and flung himself on his victim, a plump girl called Nastya (Eddie-baby did not know her surname) from behind, and seized what might have been approximately called her breasts. The girl tried to wriggle free, but she could not shout very much because then she would have been heard in the classrooms, and punishment awaited those who skipped classes; she scratched, and squealed quietly. Stimulated by the resistance and once again following the example of Prikhodko, who at that moment was pressing the truly full-breasted Olya Olyanich up against a wash-basin (she was already fourteen) and had his hands under her skirt, the new Eddie-baby also put both hands under Nastya's school-uniform skirt and gripped her in the place where girls have their «cunt». Eddie-baby had learned the word cunt» in his second year at junior school and knew where the cunt was located.

In his second junior year his classmates Tolya Zakharov and Kolya, nicknamed «Backstreet Scrounger» (his other nickname was less complicated and more humiliating—it was «Pisser»; the kids used to say that he still pissed himself, that is to say wet his bed). had tried to rape Lara Gavrilova. They had tried to rape her during long break on a heap of overcoats. In those days the school had not yet installed coat-hooks and a changing room, and the coats simply lay in a pile on the back benches. Today's Eddie-baby, aged fifteen, recalls this incident and can't understand how two eight-year-old boys could have «tried to rape» an eight-year-old girl. «What with?» smirks today’s Eddie. What sort of a penis could an eight-year-old boy have, even if he were as much of a tearaway as Tolya Zakharov and Kolya the Pisser? Tolya and Kolya were expelled from school, but two weeks later they were taken back again.

Eddie-baby seized Nastya by her «cunt» under her skirt. It was very warm where Nastya's cunt was. Eddie-baby grasped this warm spot and squeezed. At the moment when Eddie squeezed her cunt, Nastya started to howl. Eddie-baby had the impression that Nastya was not only warm there but wet too. No doubt she just finished pissing, guessed Eddie-baby.

The girls' cries, although they were not loud, brought in the cleaning woman Vasilievna, wife of Vasya the school porter (they lived in a small house in the school yard), who began walloping the boys with a wet cloth, shouting that they were «mad dogs» and ought to be in prison. «Clear off!» shouted Prikhodko. Letting go of the girls and shielding themselves with their hands from Vasilievna’s cloth, he and Eddie-baby tore out into the corridor and raced away.

*

After that incident in the girls» toilet, Eddie-baby earned the unconcealed amazement and patronizing approval of Prikhodko. It was then, too, that Eddie-baby began to be friends with Chuma the Plague—Vovka Chumakov—and in March ran away with him to Brazil.

Their escape to Brazil became widely known throughout No. 8 Middle School owing to pure chance. When they ran away to Brazil, Eddie-baby and Chuma the Plague hid their satchels under some pieces of rusty iron in the cellar of the house where Chuma lived, because why should anyone need a satchel in Brazil? God knows why they didn’t throw their satchels away altogether instead of carefully hiding them; they were not proposing to come back to Kharkov from Brazil.

At all events, the satchels were found by some electricians who had gone down to the cellar to repair the wiring, and were triumphantly brought by them to the school and handed over to Rakhilya, the boys' form mistress. By then a search was already under way.

When recalling his escape to Brazil, today’s Eddie-baby smiles condescendingly. One's first naive experiments. Why they had to go to Brazil on foot and by compass, he now has no idea. At the time, he and Chuma had set off to the south. Naturally they soon got lost, and instead of Brazil they reached the municipal rubbish-tip, ten kilometres out of town, where tramps and cripples robbed them and seized their entire capital—135 roubles and ninety kopeks—which they had saved up for their escape to Brazil, leaving them with nothing but a couple of geography text-books; Eddie-baby had brought these in order to keep up his own and Chuma's determination to reach Brazil by looking at the photographs and drawings of tropical animals and birds and the torrid landscapes of Amazonia. One of these books was called «A Journey through South America».

It was the end of March and still very cold, although the snow had all gone during a thaw in February. Without money—thus Chuma (son of a laundress and the more practical of the two) reasoned to the still obstinately romantic Eddie-baby as they sat round a campfire burning in an old steel barrel—they would never reach Brazil. They couldn't even reach the Crimea, where Eddie- baby proposed to wait till the really warm weather began, and then move by compass westwards to Odessa, where they would sneak aboard a ship going to Brazil. «Let's go home!» said Chuma.

Eddie-baby didn't want to go home; he was ashamed of returning. Eddie-baby was much more obstinate than Chuma. Without a compass, Chuma the Plague set off in the direction of a bus-stop, while Eddie-baby stayed and spent the night, stripped down to his singlet, beside the steam-raising boiler in the boiler- room of a large block of flats. Mice or rats were rustling in the corners and Eddie-baby never closed his eyes. Next morning he was caught by the sales-girls when he tried to steal a loaf in a bakery shop, and was handed over to the police.

*

Today's Eddie-baby is standing in front of his house. No. 22 Transverse Street, but he very much doesn't want to go home or to Aunt Marusya. For this reason, having stared for a while at Aunt Marusya’s lighted windows on the first floor, he decides to pay a visit to the benches under the lime trees; maybe some of the boys will be there, and perhaps they can all have a drink and a chat. Therefore, zipping up his yellow jacket to the throat, thrusting his hands into his pockets, Eddie-baby sets off boldly for the Saltovsky Road, choosing to go by the asphalted path that leads past Karpenko's house. Near Karpenko's house there is a large, stinking public lavatory. If all he wanted was a «leak», he would have stood against any wall—manners are unpretentious in Saltovka—but unfortunately he wants to do a «big job» as Eddie's parents say, or to «dump a load» as Karpenko says, or to «shit» as the rudest inhabitants of Saltovka put it. Eddie-baby is indeed shy of uttering aloud this latter definition of a daily physiological process because it is so rude.

The lavatory is a stone hut with two entrances, male and female; it is practically the only public lavatory on this, «their», side of the Saltovsky Road. Eddie-baby can't bear going in there, but since he is now spending the greater part of his time on the streets (his father and mother recall with nostalgic longing, as for some Paradise Lost, the era when he could not be forced out of doors), he is obliged to utilize this convenience.

Pushing open the wooden door, Eddie-baby sees with horror that the entire floor of the lavatory is awash with a mixture of half water, half urine, and that some anonymous folk-genius has laid a temporary causeway across the liquid, made of bricks brought from outside, leading to the wooden eminence in which three holes are cut. Trying not to breathe the noxious air, Eddie-baby balances his way along the bricks over the turbid midden, and, after lowering his trousers, sits down on one of the holes. Since he is nevertheless obliged to breathe now and again, Eddie-baby is made involuntarily aware that the stench is compounded not only of urine and excrement, but also of vomit. The opposite end of the wooden eminence is covered in a thick layer of vomit. The vomit is an artificial red in colour: obviously the victim who left the contents of his stomach here had been celebrating the forty-first anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution by drinking exclusively Cahors or Strong Red. Specialists or professionals—and Eddie-baby is a professional—consider that fifty per cent of Soviet Strong Red wine actually consists of dye and that it corrodes the stomach of any idiot incautious enough to drink it.

Eddie-baby tears off from a rusty nail on the lavatory wall a scrap of newspaper, which some kind soul—and such there will always be—has left there, and wipes himself, recalling with a chuckle the theory propounded by Slavka the Gypsy that the printers» ink on newspaper is harmful to the arsehole, and that from constant wiping of it with newsprint one can get cancer of the rectum.

Today the lavatory is so repellent that Eddie-baby hurries to get out of it as quickly as possible, but he makes an unpardonable mistake. Standing up to throw the paper in the hole, he unintentionally looks down and notices that the level of shit under the dais is unusually high, that no more than ten or fifteen centimetres separates the shit from the seat and that here and there pinkish-white worms are squirming around in it!

«Fuck this!» exclaims Eddie in horror, and hurries over the bricks away and out of the disgusting cloaca, cursing himself for having looked down. After putting fifty metres between himself and the revolting, lighted building, he sighs with relief.

On the benches under the lime trees, to his delight Eddie-baby unexpectedly finds not only Cat and Lyova, but Sanya Krasny too, who somehow oughtn't to be there.

Standing between Cat, Lyova and Sanya are a half-litre of Stolichnava vodka and a white bowl full of cucumbers and slices of roast meat. The bowl has obviously been brought by Cat and Lyova, whose house—No. 5—is nearby. Sanya’s house is closer to Eddie's.

«Ed!» the three lads shout with delight.

Eddie-baby does not call out in reply but goes up to them, smiling and silent. He knows that if he responds with «Yes!» or «What?», all three heroes will shout back in unison: «Go suck a cock for lunch!» and roar with laughter. Eddie-baby is never offended by this; it is a traditional, jocular greeting, but remembering it, he refrains from replying.

To be fair, it should be said that the same relationship exists between Cat, Lyova and Sanya. If Sanya calls out «Cat!» and if Cat forgets himself and replies «What?», then he will get the invariable response: «Fuck you in the mouth!» and a roar of laughter. It is a friendly if coarse joke, nothing more.

«Sit down, Ed,» says Sanya. «Lyova, pour the boy a drink.»

Lyova pours out Eddie-baby half a glass of vodka. Eddie drinks the cold, biting liquid. Having downed his vodka, Eddie-baby pauses, then says nonchalantly to Sanya: «Didn't you go to Rezany's party, Sanya?»

Only after he has spoken this sentence does Eddie-baby allow himself to stretch out his hand for a piece of meat and a cucumber. Never to be in a hurry is a sign of the utmost cool when drinking.

It turns out that although it is only half-past nine, Sanya has already managed to have a furious row with Dora, his hairdresser girl-friend, has told her to go to hell, slapped her face and left Tolya Rezany’s party slamming the door (Tolya is also a butcher, with whom Sanya and Dora generally celebrate holidays); now Sanya is sitting on the bench under the lime trees. Where else should a young man from Saltovka go, where else to take his grief and troubles, and who is there to console him if not his cheerful friends and a good glass of vodka?

«Fucking slag!» says Sanya, referring to his abandoned hairdresser, as he chews a cucumber after his vodka. «Tries to make out she's a virgin. Abanya told me a month ago that Zhorka Bazhok, a guy from Zhuravliov, was fucking her. I didn't believe him, but now I see Abanya was right!»

«You ought to dump her altogether, Sanya,» says Lyova. «Mean to say you can't find yourself another cunt? You only have to whistle and a dozen of them'll come running.»

«Ask Svetka,» says Eddie-baby in support of Lyova, meaning Sanya's sister Svetka. «She's got a whole heap of girl-friends, she'll pick one out for you.»

«Why the fuck should I ask anyone?» Sanya objects, slightly offended. «I only have to walk into a dance and every cunt in the place is looking at me, waiting for me to invite them out and fuck them. As for my sister Svetka»—here Sanya turns to Eddie—«she's still wetting her bed, and her friends are more your age, Eddie. As far as I'm concerned, they're just kids.»

Eddie-baby says nothing. He is ashamed that he's still a kid.

Crunching their cucumbers, the group falls into a melancholy silence. Now and again they can hear a drunken song, snatches of music or a burst of laughter coming from the neighbouring houses.

«Well, how about getting another bottle?» Cat breaks the silence, speaking to Sanya.

«OK, why not . . . ,» Sanya agrees and fumbles in his pocket for money. «No. 7 Grocery is open till midnight tonight.»

«I've got some cash.» Cat stops Sanya. Cat's a decent lad and earns good money in his factory. As a butcher, of course, Sanya earns far more, on top of which he always has plenty of meat, but he also spends his money fast. Cat wants to do the honours now, which is his right, so Sanya doesn’t object and takes his hand out of the pocket of his Sunday-best Hungarian overcoat.

Cat gets up from the bench, pulls on his jacket (he and Lyova came out without overcoats), says: «OK, I’ll be back in a minute», and sets off.

«If they've got any Zhiguli beer, buy a couple of bottles,» Lyova calls after him as he goes.

«OK, Fatty,» Cat replies without turning round.

*

After taking only a few paces, however, Cat stops and stares hard in the direction of the tram-stop.

«Hey, boys, it’s a pig,» he announces, «running this way!»

«Fuck him, let him run,» says Sanya calmly. «We don't owe him anything. There's no more vodka left. He's wasting his time running.»

Heavy boots thumping, greatcoat unbuttoned, a policeman comes running towards the benches. Eddie baby knows him, as do the others. Stepan the pig, a man of around fifty, cannot of course be a good man, but Stepan Dubnyak is not a complete shit, though he's a crafty one. If he ever gives any of the lads fifteen days in the cells for being drunk and disorderly, he always brings them a bottle in his pocket, although drinking in the cells is naturally not allowed. Several times Stepan has managed not to arrest boys when he should have arrested them, and so on. Stepan wants to live at peace with the local tearaways.

Now that Sanya has stopped working at the Horse Market and moved to the new food-store on Materialist Street, the same one that Eddie-baby and Vovka the Boxer once robbed, Stepan's wife goes to Sanya to buy meat. He puts aside some nice pieces for her. Or he says they're nice. Sanya likes to make fun of his customers. One day for a bet, in Eddie-baby's presence, he pulled out the thick red lining from someone's galoshes, hacked it up with a cleaver on his wooden butcher's block, smeared it in blood and there and then sold it—all of it—as a makeweight to someone's order of meat.

«What's the matter, Stepan?» Sanya asks in a phoney-sympathetic voice. «Are the dogs after you?»

«Help me out, lads, please!» Stepan blurts out, panting. «Some black-arsed buggers in the 12th Construction Battalion have mutinied. They were smoking hash and now they’re moving this way up Materialist Street towards the Stakhanov Club. They’re beating up everyone in their way, they've already raped one girl . . . and they're coming this way! They beat up my mate Nikolai, he’s unconscious, I had to leave him in the club . . . .»

Judging by Stepan's face, the matter is serious. He has a terrified look, and he's not easy to frighten.

«How many of them are there?» Cat asks. «Is it the whole battalion?»

«There were about twenty,» says Stepan, breathing heavily. «Now there are about ten or a dozen of them. All Uzbeks. But the ringleader is a sergeant—he's Russian. Obviously their relatives brought them this hash from Uzbekistan for the holiday. They're completely insane, foaming at the mouth . . . .»

«Why the fuck should we stick our necks out,» growls Lyova, «just to help the pigs? I've done time, thanks to you pigs, so you can count me out.»

«Are they armed?» Sanya asks Stepan, disregarding Lyova's grumbling.

«No, thank God. They've taken off their belts and are swinging the buckles as weapons. They're beating up everybody, doesn't matter if it's women or children. Help me, lads, I'll never forget it if you do! There's no one at the station except the duty officers, and by the time they've called up some help from the other stations, God knows how many people these black-arsed bastards will have injured!»

«Well?» asks Sanya, speaking principally to Cat. «Shall we help the forces of Party and government in the struggle against the black-arsed hooligans?»

Eddie-baby, glancing at Sanya, realizes that he needs a target on which to vent the fury he feels for Dora the hairdresser.

«Party—hell! Government—hell! They're bashing up your own girl-friends. They've just gang-banged a girl in the park!» shouts Stepan.

«If they caught my slag she'd love it!» laughs Sanya.

«Come on,» Cat agrees, «let’s go.» He doesn’t ask Lyova, knowing that he’ll come with them anyway.

They all run after Stepan, across the tram-tracks and into the darkness beyond. Stepan is followed by the hefty twenty-two-year-old Sanya; the powerful Cat, heavy as the bar-bells that he lifts; Lyova; and Eddie-baby, though nobody asked him to come and he is slightly afraid.

At the poorly-lit Stakhanov Club (closed because it is a holiday), a couple of frightened old caretakers inform Stepan that the drugged, mutinous soldiers did not head for the Stakhanov Club as Stepan had expected, but have for some reason run on towards a practically deserted and uninhabited region in the direction of the Saburov dacha. The area is bounded on one side by the fence surrounding the Hammer and Sickle factory that extends for several kilometres; along the other side is the fence of the Piston factory, while between and parallel to them runs the tram-line along which the trams carry people to and from Saltovka.

It is quite possible, thinks Eddie-baby, that the soldiers have simply lost their way, because there is absolutely nothing for this horde, drug-crazed by some Asian narcotic, to do there. However, beyond these two kilometres of wasteland, covered as it is with several years» growth of weeds and marshy in places, there are more residential suburbs and after them there is the town. Perhaps the soldiers want to go to the town?

«Where are your fucking vigilante squads today?» Sanya shouts to Stepan. Elbows working like pistons, they are running in the direction pointed out to them by the club caretakers, as they attempt to catch up with the band of savage nomads.

«They’re fucking useless!» shouts Stepan in despair. «None of them wants to go on patrol on a public holiday.»

For some time, breathing noisily, they all pound away in silence past the fences that flank the open space. The numbered sections of steel fencing flash past: two, three, five, seven . . . twenty and more, Eddie-baby counts to himself.

*

At the point where one fence meets the other and the narrow asphalt path suddenly turns towards the tram-tracks in order to cross them, the little group is met by a terrifying howling sound and several flying stones. It is not even a howl, but more of a concerted roar, something like a distorted «Hurra-a-a-a-h!» coming from throats invisible in the darkness.

«Oh fuck!» Stepan curses angrily but impotently as he ducks away from the cobble-stones, heavy as cannon-balls. Stepan's voice quivers, as if he is crying. «We'll never smoke them out from here! Just our luck that those fucking workmen haven't finished repaving the road.»

The black-arsed buggers have taken cover behind a readymade barricade of cobble-stones, a metre and a half high, left behind by road workers, who are now probably out drinking somewhere, not even suspecting what is happening at their abandoned workplace. Stepan, Sanya, Cat and Lyova, followed by Eddie-baby, beat a forced retreat out of range of the heavy cobblestones and hold a conference.

«We must arrest them before the police cars arrive,» says Stepan.

«Not fucking likely,» Sanya objects. «The most important thing is to get that sergeant, and then all the rest will run away.»

«Get him, get them!» The policeman sneers at Sanya, imitating him. «How? There are four of us, and at least ten of them.»

«Five of us,» Eddie-baby puts in grimly and firmly, pushing his way into the circle, but no one pays him any attention.

«Why don’t you shoot, you cunt?» Sanya asks Stepan. «What the fuck d'you think they give you a TT automatic for? So you can catch villains with your bare hands?»

I can’t!» says Stepan firmly. «If I kill someone and he's unarmed, and a soldier into the bargain. I'll be put on trial. I can't shoot.»

«You prick!» Sanya says bitterly. «Just shoot and they'll shit themselves. We re all witnesses that you were firing in self-defence. If you're afraid of killing one of them, aim at their legs . . . .»

«I can't!» Stepan cuts him off. «I can't.»

«Well, give me the gun then,» says Sanya, «and I'll get that sergeant.»

«I can't entrust a police automatic to you!» Stepan is losing his temper. «Are you joking?»

«You prick! Oh, you prick!» Sanya curses him.

Their argument is interrupted by an outburst of roaring and a hail of stones. This time the situation is far more serious. The maddened soldiery have run out from behind the barricade and are advancing on them. Eddie-baby catches sight of them for the first time. Only a few of them are in greatcoats, despite the cold. Lacking belts to tighten them, their uniform tunics are hanging around them like peasant shirts, collars open, baring their white undershirts that emphasize their dusky oriental features. Wrapped around his right hand, each one of them has a wide, army-issue belt with its heavy cast-bronze buckle. Anyone getting one of these buckles on the temples or the top of the head usually falls unconscious. Fighting with belt-buckles is a normal army pastime. The soldiers are now running straight at them, swinging their belts in the air.

Sanya, Cat and Lyova, the latter limping, pick up the cobblestones thrown by the soldiers and hurl them back. Eddie-baby follows their example, without much success. As in a slow-motion film, Eddie-baby sees the swarthy, infuriated faces getting dangerously larger.

A hitherto inaudible tramcar rolls up and comes to an enforced halt, furiously ringing all its bells; it can go no further—some of the soldiers are running across the tram-lines, and several large cobblestones are lying right on the tracks.

The soldiers are now fewer in number than the young men and the policeman, who are hiding behind bare tree-trunks at about ten metres distance. Stepan's trembling fingers are poised over his holster.

«Shoot, you prick, or they'll smash us all—shoot!» shouts Sanya.

Cat seizes Stepan by the arm and tries to take the revolver from him. Stepan wrenches his arm free. He holds the revolver at arm's length. It is shaking in his hand. Stepan is terrified.

«Shoot!» shouts Sanya.

«Shoot, you cunt!» Lyova shouts in fury.

«Shoot at their legs!» yells Cat.

«Shoot!» shouts Eddie-baby.

Accompanied by the unceasing carillon of tram-bells, the police sergeant finally presses the trigger several times in succession. «Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!» Four shots resound in the night air and four times the invisible bullets strike sparks from the cobbled roadway under and between the feet of the band of soldiers, bringing it to a sudden stop.

Clustered behind Stepan, the lads see the soldiers running back into the darkness to seek cover behind the barricade. In a shower of sparks a second tramcar, also ringing its bell, stops behind the first one. The doors are closed, the passengers press up against the windows.

Stepan fires a few more rounds and changes the magazine.

Not all the soldiers have taken cover behind the barricade. One large figure stops, as though having second thoughts, then utters a desperate roar: «A-a-a-h!» and again sets out towards Stepan and the lads.

«The ringleader!» says Stepan hoarsely. «The sergeant!» and staggers back.

«He’s the one we want,» says Sanya. «Distract his attention, Stepan, annoy him, while Cat and I sneak round along the fence and then grab him from behind. He's in such a state, he won't notice what we’re doing.»

Cat and Sanya drop on to all fours and make for the fence, keeping close to the ground.

The sergeant is no longer running but advancing ponderously towards the retreating Stepan, Lyova and Eddie-baby.

«Shoot, you bastard!» shouts the sergeant. «Shoot, you rotten fucker! Go on, shoot at a Russian soldier, sodding police bastard!»

«Give up, you stupid prick, or it'll be the worse for you!» Lyova shouts to the sergeant. All three, including Eddie-baby, retreat before the advancing hulk of the sergeant, waiting for the moment when Sanya and Cat will jump him from behind.

Suddenly the tramcar driver switches on his headlights and the whole scene is flooded in yellow light. The sergeant ceases to be a massive, dark figure and can at last be properly seen. He stands there, his uniform tunic pulled open with both hands to bare his chest; despite the cold, drops of sweat can even be seen on his forehead. Unlike the soldiers, whose heads are shaved bare, his red hair is clipped in a crew-cut. He comes nearer and nearer. Nervously Stepan waves his TT pistol, holding it out as before at arm's length.

«You prick! You can't do it!» Lyova shouts at the police sergeant.

What can't he do? wonders Eddie-baby. At that moment, glancing at Stepan, almost bent double as he points his TT forward, Eddie-baby realizes that Stepan is not very good at shooting. I wonder if Stepan was at the front in the war? Eddie thinks.

«Shoot me in the chest, you pig! Shoot a Russian soldier!» The sergeant keeps shouting in a senseless, animal-like roar. Suddenly he bends down and picks up a cobble-stone at his feet and raises it over his head.

«I'll kill you!» he shouts in a wild voice and lunges forward, only to crash to the ground, together with the stone, under the weight of Cat and Sanya, who have flung themselves on him from behind.

This time silently, the soldiers dash out from behind their fortification in a bid to rescue their leader and superior officer, but Stepan fires at their legs again, this time more coolly, once more striking beautiful yellow sparks off the roadway.

Almost at that very moment the scene is enlivened by the sudden arrival of three police cars. Policemen jump out of them and attempt, under Stepan's leadership, to catch the soldiers. Simultaneously both tram drivers open the doors of their cars and a crowd of slightly drunken men, dressed in their holiday-best, leap out and try to discover what's going on.

Eddie-baby hears his name: «Ed!» It is Sanya calling him. He has obviously been calling for some time, as he sounds angry.

«Ed, you mother-fucker! Come here.»

Eddie-baby runs towards the voice.

Sanya and Cat are holding down the giant, defeated Russian sergeant. The giant is croaking and trying to move. In spite of Sanya's hundred kilograms and Cat's trained muscles, they are clearly not finding it easy to keep the sergeant immobile.

«Ed, where the fuck have you been?» Sanya says in a slightly more friendly tone. «Pull the belt out of this bugger's trousers!»

Eddie-baby cautiously pushes the sergeant's tunic upwards and unbuckles the belt on his trousers.

«Don't touch me you little bastard, or I'll kill you!» the sergeant croaks through his bloodstained mouth.

«Shut up!» Sanya addresses the sergeant almost affectionately and punches him in the face from above as though with a hammer. Sanya’s punch weighs several pounds and his hand is hard. Sanya constantly toughens it by hitting the edge against a hard surface, so that he can easily smash a plank of wood with it. The sergeant falls silent.

«We’ll just go and take a look around, and you, Ed, stand guard on this criminal,» says Cat sarcastically. He is clearly amused at playing the role of a guardian of law and order. Seeing the nervous glance that Eddie-baby is giving the sergeant, he adds: «Don't be afraid of him. If anything happens, kick him in the throat or the face with the steel tip of your boot.»

«And don't feel sorry for him,» adds Sanya. «If he gets loose he won't have any pity on you.»

*

Several policemen, along with Sanya, Cat, Lyova and Stepan return to the scene of action, where they lift the sergeant from the ground and stand him on his feet. Only now does Eddie- baby appreciate how unusually tough the sergeant is. Sanya and Cat grip him by his arms, still tied behind his back, and lead him towards one of the police cars.

But Stepan has other plans. He stops the lads, and, taking Sanya aside from the other policemen, says to him in a half-whisper: «Listen, Sanya, don't be a fool! The sergeant is yours and mine. These boys have just come to collect all the credit when we did all the work»—he says, nodding towards the other policeman. «What we must do is take the sergeant to the station ourselves and hand him over directly to Major Aleshinsky.»

Stepan stops for a moment, then, changing his business-like tone to one more confidential, he goes on: «Major Aleshinsky has got his knife into you, Sanya. But when we turn up with this package of goods»— Stepan nods at the sergeant—«he'll change his mind. Perhaps even arrange some official reward: «For collaboration with the police force in the maintenance of law and order.» Well?»

«OK, let's go to the station,» Sanya agrees, though not very willingly.

The pigs don't object, so Stepan quickly forms a little procession. Stepan and Cat take the lead, each holding an arm of the arrested Uzbek soldier. His tunic is torn at the shoulder and soaked in blood. He looks frightened: obviously the effect of the drug has started to wear off, and now he realizes that something not very pleasant has happened. Behind the Uzbek come Sanya and Lyova. The inquisitive Eddie-baby—first running ahead a bit, then dropping back—brings up the rear.

The assembly is accompanied by a dozen or so extraneous civilians, largely made up of drunken passengers from the two tramcars, eager for sensation.

*

Eddie-baby notices from the behaviour of his older comrades that they really want to be off somewhere else as quickly as possible: further developments are of little interest to them, despite the exotic temptation of appearing in front of the chief officer of No. 15 Precinct not as tearaways or criminals but as conscientious auxiliaries of the police in the struggle against crime.

Cat is the first to duck out. Eddie-baby sees him hand over the arm of the Uzbek soldier to a keen little man in a white cap and a shabby raglan raincoat. The little man grasps the arm with ferocious willingness. Free and glad of it, Cat drops back a little and for a time walks alongside Sanya and Lyova, whispering something to Lyova, obviously telling him to detach himself from the procession. Indeed, a short while ago Lyova had loudly announced that he needed a leak, and now he hands over his post as escort to yet another onlooker who is eager to take part in the event: a Georgian of criminal aspect delightedly seizes hold of the sergeant's rock-like biceps.

Eddie-baby's observations are interrupted by Sanya, who says to him, quietly so that neither the giant sergeant nor the Georgian will hear him: «Ed, take this animal to the police station—but whatever you do, don't go inside, got it? I'm going to . . . take a leak too.» Sanya gives Eddie a meaningful look, winks, and disappears into the crowd.

Eddie-baby doesn't understand why his friends should want to forgo the triumph that they have all earned. Why were the lads refusing to go to the police station and for the first time present themselves to the dreaded Major as heroes instead of criminals and culprits? Stupid! thinks Eddie-baby. Stupid. The next time one of them is booked, the Major might have to let him off. After all, the police are always lenient if one of their regular vigilantes gets mixed up in any trouble . . . .

Later, however, when they reach the 15th Precinct stationhouse—built, like almost all the houses in Saltovka, out of white brick—Eddie-baby feels certain inexplicable pangs of conscience. He stays outside, pretending to dawdle and allows the Georgian the honour of squeezing through the door with his prisoner, the granitelike sergeant. All the onlookers, too, crowd into the entrance lobby of the station. Eddie stands by the doorway for a minute or so, then calmly goes away. Sensible Eddie.

Translated from the Russian by Michael Glenny