This book is dedicated to all those who once lived in Russia and patiently told us the stories of their lives.

Slava Kurilov, Galina Nikolayevna von Meck, Professor Elizabeth Kutaissova, Sofia Sergeyevna Koulomzina, Pyotr Petrovich Shilovsky, Alexandre de Gunzburg, Anna Alexandrovna Halperin, Count Alexei Bobrinskoy, Ivan Alexandrovich Yukhotsky, Nadezhda Ulanovskaya, Count Alexei Bobrinskoy, Irina Yelenevskaya, Professor Yekaterina Alexandrovna Volkonskaya, Natalya Leonidovna Dubasova, Anastasia Valentinovna Becker, Arvids Jurevics, Alexander Vasilievich Bakhrakh, Pyotr Robertovich Karpushko, Marc Mikhailovich Wolff, Countess Olga Bobrinskaya, Countess Yekaterina Petrovna Kleinmichel, Esther Markish, Countess Natalya Sumarokov-Elston, Metropolitan Anthony Bloom, Oleg Olegovich Pantyukhov, Margarita Ivanovna Freeman, Viktor Petrov, Ivan Alexandrovich Yukhotsky, Irina Ilovaiskaya-Alberti, Vladimir Alexeyevich Grigoriev, Boris Georgievich Miller, Georgy Mikhailovich Katkov, Vera Fyodorovna Kalinovska, Michel Gordey, Countess Ekaterina Nieroth, Countess Natalya Sumarokov-Elston, Iona Solomonovich Halperin, Pyotr Robertovich Karpushko, Tatyana Ivanovna Gabard, Dmitry Vladimirovich Lekhovich, Pyotr Petrovich Shilovsky, Olga Petrovna Lawrence, Natalya Leonidovna Dubasova, Lady Masha Williams, Professor Alexander Kennaway, Vassily Arkhipovich Sokolov, Arvids Jurevics, Gershon Solomonovich Shapiro, Yakov Samoilovich Kaletsky, Iosif Emanuilovich Dyuk, Valery Andreyevich Fefyolov, Vsevolod Borisovich Levenstein, Katja Krausova, Mikhail Leonidovich Tsypkin, Nina Abramovna Voronel, Vitaly Komar, Eduard Limonov, Zhores Alexandrovich Medvedev, Leonid Vladimirovich Finkelstein, Vladimir Viktorovich Goldberg, Kirill Uspensky

The Other Russia:

The Experience of Exile

Michael Glenny and Norman Stone

// London, Boston: «Faber and Faber», 1990,

paperback + dust jacket, 496 p. (XX+476),

ISBN 0-571-13574-9,

dimensions: 203⨉127⨉25 mm

// London, Boston: «Faber and Faber», 1990,

hardcover + dust jacket, 496 p. (XX+476),

ISBN 0-571-13574-9,

dimensions: __⨉__⨉__ mm

// New York: «Viking», 1991,

hardcover, dust jacket, 494 p. (XX+474),

ISBN 0-670-83593-5,

dimensions: __⨉__⨉__ mm

Acknowledgements

For reasons of space and editorial exigency it has been possible to include only approximately one-third of the contributions so willingly provided by our informants. The authors wish to thank all those who told us the stories of their lives; even if they were not incorporated into the final published text, every contribution without exception was of the greatest value in enabling us to build a total picture of Russian emigration since 1917. Without this, it would have been impossible to write this book.

The authors' special thanks are due to the Markish family: Madame Esther Markish, Dr Simon Markish and Mr David Markish, whose generous help in enabling the authors to meet a large number of their informants greatly assisted the gathering of material for this book.

The authors are grateful to Christine Stone, whose idea this was and who has been extremely helpful with the long job of editing; Louise Pirn, who helped to shape a very difficult manuscript; Brenda Thomson, who after heroic labours put the manuscript into its final form; Richard Davies of the Leeds Russian Archive; Professor Marc Raeff; Sir Isaiah and Lady Berlin; Dr Harold Shukman; Dr Michael Heller; Mr and Mrs Kirill Fitzlyon; Professor and Mrs Lionel Kochan; and the staffs of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London.

Norman Stone

Michael Glenny

October 1989

57. No Free World

Eduard Limonov

Eduard Limonov was born in 1944 in Kharkov, the son of a Soviet Army officer. He became a novelist and, as his books could not be published in the USSR, emigrated to the West.

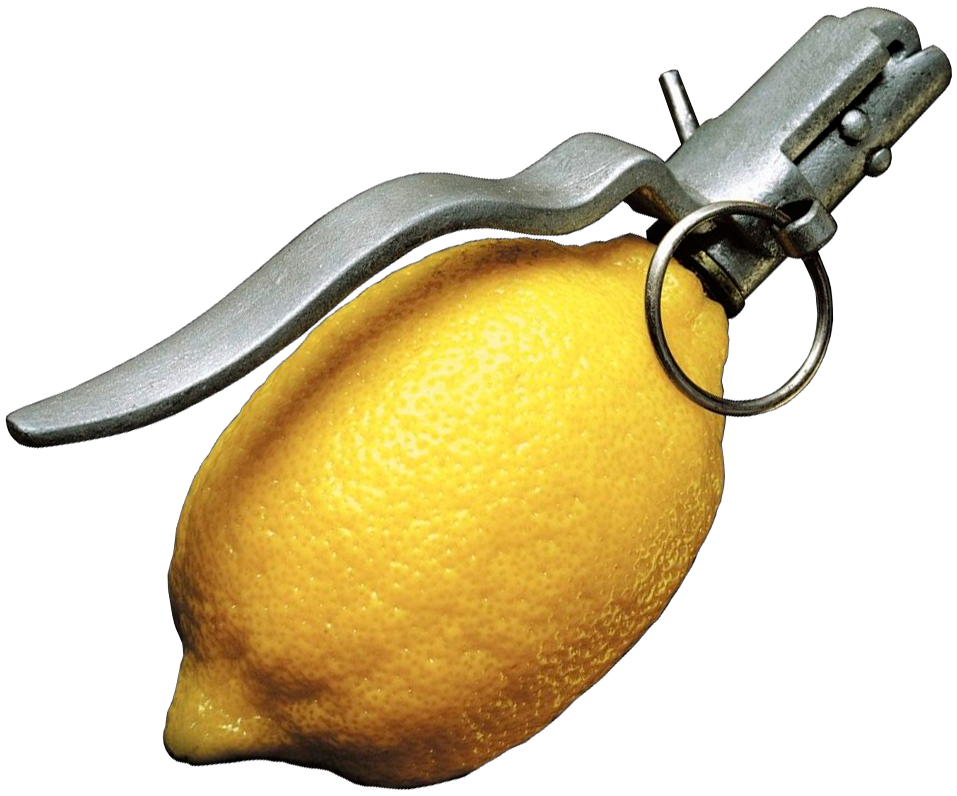

I feel great because my name is a kind of punk name. I adopted it in 1964 when no punk movement existed, when I was twenty, and at the end of the 1970s I discovered that it was very fashionable to have a name like that — Sid Vicious, Johnny Rotten . . . ! Eduard Limonov is less frightening, but it's artificial enough. In Russian, it sounds even more artificial than it does in English [it derives from the Russian word for «lemon»]. It indicates acidity. One of the critics at «L'Express», when my book «It's Me, Eddy» came out in French, wrote that if the name was not invented there must have been some stroke of destiny, as the pages of my novels were so acidic.

Russian émigré writers often refuse to learn the new language. There are many reasons for that. There is the traditional Russian laziness — it’s a kind of character trait that gives Russian conservatism an immovable quality. It's very difficult for them to organize themselves — especially for the generation of Sinyavsky or even Maximov1. If you come here after the age of forty, I think that to learn the language requires a persistent sacrifice of time. It requires study every day, and reading. I don't think that writers who were already distinguished wanted to bother themselves with it. Yes, it's irrational, but I think that's the reason — they think it's better to write new books than to learn the language. Myself, I'm learning French actively. I spend four hours a day and now read with little difficulty. [If you do not learn the language you cut yourself off.] For example, Maximov has no information at all about the Western world. What information he has is from his secretary, who gives him some descriptions or short translations of what he needs, but it's not possible to cover everything. I heard that he desperately tried to learn the language, but was not successful, and he complained that he was too old. That's not true, because he came here when he was almost the same age as I am, and I have been reading French books for nearly two years.

I have no active contact with Maximov, and just a little with Sinyavsky. I think it's suicidal — if they cannot overcome their weakness. They are rejecting the possibility of existing in the present — they can exist only in the past. You cannot take Maximov's political speeches seriously because he doesn't know what he's talking about. If he doesn't read the «New York Times» or «Le Monde», he's not an intelligent man. He's not informed.

I don't know him to the extent of talking about his psychological structure and how he behaves. I have met him a few times. I think he's a creation of «dissident fever». He's a creation of the Western world, together with some internal conditions in Soviet society. In the USSR he was a typical writer of the Right. He was a writer for the magazine «October». He's still a writer of the Right. He automatically changed camps, just as the KGB defectors change camps to the CIA. It's natural. He's just a malcontent — because he was dissatisfied with his personal position in the Soviet hierarchy. It has nothing to do with the political structure and it seems to me that most of the dissidents are in the same position. The ageing writer suddenly discovers that he is not satisfied with his achievements. We are not talking about the influence of Soviet internal policies on writers.

I never felt strongly that I belonged to any nation, even to Russia. I never wanted to go to America. Even in Russia I had advised the friend who had invented my name that he should not go to America. I said, «Go to America only if you have no other possibility. Otherwise stay away from that country.» I remember my image of the United States. I was a bit afraid of the country. I remember Konstantin Leontiev's2 philippics against the bourgeois of the world, and I thought about the United States as a country where the bourgeois is on top, and I have never had a good relationship with that social class.

I didn't want to go to the United States, but I had no choice. When I was in Vienna, I applied for a visa for England . . . I didn't want to leave Europe. I decided on England because I had some friends there who wanted to give me an invitation, but to get a visa I would have had to wait at least six months. In Vienna I needed to receive some sort of Austrian temporary document. I had no documents; everybody who leaves the USSR has none. I was waiting there with my wife — I had been married in the USSR — and she was very scared of Vienna in November. It was very rainy, cold and empty, and not very friendly, so we decided to go to Rome and to forget the idea of going to England. In Rome we had a choice of only the United States or Canada. We felt it was better to go to New York than the forests of Canada . . .

In Vienna we had been supported by the Tolstoy Foundation, as is usual for émigrés, [and it was through them that we went to New York]. I had a very awkward relationship with them, and I didn't like the personalities of the people, because they were so far away from me. I found them very peculiar and strange; they were all half Russians, never actually very well adapted into American society. Some of them were Americans. Irish and so on — the scum of society, or what one might call losers. They have a circle of interests that are completely strange to me; they have very old-fashioned habits. I read about such people in Soviet books — they belong to the nineteenth century in my opinion. But objectively, they did something for me.

From another point of view, the Tolstoy Foundation was responsible for all the American propaganda taking people out of the Soviet Union. I even think that one day some bright émigré will go and sue, if not the United States, then one of the organizations like Radio Liberty, or Voice of America, or Radio Free Europe, to show the damage they did to his life, because a lot of people would actually be better off in the Soviet Union. All those material losses, like losing their place in Soviet society, and the hardship of finding a place in the new society . . . maybe one day someone will be able to prove it. Anyway, the Tolstoy Foundation paid for that propaganda. If you push the people out of their own country, then you have to pay.

I remember, for example, in 1968 at the time of the invasion of Czechoslovakia, I'd been listening to Western Russian-language broadcasting, and all the time they would be relaying the news of the invasion of Czechoslovakia in every possible detail. At the same time there was the Vietnam War, and there was no information about that. There was some information in the Soviet press, but traditionally we didn't believe it. That is the difference between the United States and the Soviet Union: the people there traditionally don't believe official information, and believe all the nonsense they hear on the foreign radio . . . The picture of the world is completely distorted by Radio Liberty — like the émigré newspapers, for example «Russkaya Mysl'», which was paid for until 1975 by the CIA and is now funded by the State Department. What can you expect from such newspapers? They are very happy about how Soviet soldiers are killed in Afghanistan, they are happy about every major or small disaster in the Soviet newspapers. They are not only anti-Soviet, but also anti-Russian.

[My first job in America was as] a proofreader on a Russian émigré newspaper — «Novoe Russkoe Slovo». All Russian émigré newspapers look alike, and sooner or later, no matter how they start, they become stupidly conservative, with not even rightist views, and every dark superstition available. They are newspapers for butchers, or backwoodsmen. I don't know any other nation that is able to produce such a press. [There was a weekly called «Novy Amerikanets»] — even in its best days it was kind of «hurrah-patriotic» and to the taste of a provincial Jewish émigré who had settled down in Brighton Beach. The strong desire to sell the newspaper made the owners and the journalists look alike; instead of trying to develop higher standards for the paper, they chose to give the people what they want now. It is even worse [than local papers], because the Western newspapers somehow belong to the population; but the émigrés are not a population but a group, and everything is more hermetic, more closed. The pressures of a free society upon journalism are ten times bigger for émigrés. If you look at American patriotism, natural patriotism, that is one thing; they can accept a certain kind of criticism, some ironic views — even the «New York Post» can do it. But the Russian newspapers cannot do it. Everything is stonily serious. I don't read them, and said goodbye a long time ago to that kind of life.

In 1977, I left the hotel where I lived with some Russian friends, and after that I never really went back to them. It happened because it happened — I've no idea of the reason. I was so outraged with that existence. I never wanted to be an émigré — I wanted to be the same as everyone else. The only difference was that I didn't know the language very well. Some of my views were more interesting than other American writers, some were absolutely the same. I didn't see any difference between me and the outside world. I did see great differences between me and the Russian émigré community. In emigration, I found myself surrounded by people to whom in Moscow I would not even talk: I would have nothing to do with people like that. I had belonged to a very closed counter-culture in Moscow — a few thousand people living their special life together, quite different from Soviet society . . .

I feel no desire to return to the Soviet Union. That is my past. My criticism of Western society is absolutely forgivable for the person who lives here — there is nothing special about it. I cannot publish my books in the Soviet Union, and with great difficulty I have published my books in the United States. But that is not the same for 265 million people, because they do not all want to publish books. They go to work every day and spend eight hours a day at work. I do not see that on the level of working-class people there is such a difference between societies; it’s only a problem of material difference. I always despise the material things . . .

Americans call their society «democratic» and «the free world». It sounds as vulgar to me as the Soviet society that calls itself «the dream of mankind» and all that vulgar shit. If it is really a free world, why should you talk about it? It's for stupid people. The unfair election is the same in the Soviet Union as in the United States, except that in the Soviet Union it's one candidate and in the United States, it's two. Look at that Democratic primary, for example, in the United States. All the candidates are not less than senators, except poor Jesse Jackson, and he will never win as everybody knows. That society's more predictable than the Soviet.

I am not desperately anti-American — not at all. I judge the country on a very personal level, and on another level, from my analysis of their society from what I saw. I didn't see it from a good window of the Hotel Americana as Solzhenitsyn saw it. I saw it from the point of view of an underprivileged member of that society. From what I remember from my welfare days, from my endless waiting for my turn in welfare centres, and later, when I refused welfare and worked as a painter, as a digger and received $3 an hour where Americans received $10 — I see that society as very hypocritical and nasty in its own way, and very dangerous as well . . .

Limonov came to France in 1980 and now lives and writes in Paris.

Notes:

1 The writers Yury Daniel (pseudonym: Nikolay Arzhak) and Andrey Sinyavsky (pseudonym: Abram Tens) were put on trial, to condemnation throughout the world, for «anti-Soviet activities» — i.e. publishing abroad. They were sentenced to five and seven years respectively. Sinyavsky emigrated to France in 1973; Daniel remained in the USSR. Vladimir Maximov, a writer of Dostoyevskian tendency.

2 Konstantin Leontiev (1831–91) was a famous anti-liberal and religious philosopher, with early training as an archaeologist.

www.limonow.de:

⟩ Eduard Limonov was born in 1944 in Kharkov…

Eduard Limonov was born in 1943 in Dzerzhinsk…