«Fyu-fyu… fyu!» A bird whistles three times. The youth Limonov sighs and grudgingly opens his eyes. Sunlight pours into the narrow room from Tevelev Square, through the big window, yellow as margarine. The walls, decorated by painter friends, always delight the just-awakened young man. Tranquil again, the young man closes his eyes.

«Fyu-fyu… fyu!» again calls the bird, then adds, in an angry whisper, «Ed!» The young man throws off the covers, gets up, opens the window and looks down. Beneath the window, by the low wall of the green square, stands his friend Genochka the Magnificent, wearing a bright blue suit, and smiling, head tilted upward, at him.

«You asleep, you son of a bitch? Get down here!» Behind the magnificent Genochka, on the emerald grass, camps a company of gypsies, breakfasting on watermelon and bread, laid out on shawls as on tablecloths.

«Rise and shine, the day is fine!» says a young Gypsy woman near Genochka, and actually beckons with her hand to the young man at the window.

The youth, placing a finger to his lips, indicates the neighboring window and, nodding his head in agreement, whispers, «Right!» — shuts the window and, carefully going to the sliding door which leads to the next room, listens. Rustling and some breathing can be heard from within, and the smell of tobacco seeps from under the door. His mother-in-law is undoubtedly sitting in her classic morning pose, with her tangled grey hair over her shoulders, before her mirror, smoking a cigarette. It seems that she, Celia Yakovlyevna, didn't hear her son-in-law's brief conversation with Genochka the Magnificent, her most fearsome enemy. Now, the young man realizes, it is time to act quickly and decisively.

Taking from the bookcase, the lower part of which has been made into a cabinet, his pride and joy, a cocoa-colored suit with gold highlights shining through the cloth, the young man quickly pulls on his pants, a pink shirt and a coat. At the head of the bed stands a card-table, and scattered over it are pencils, pens, paper, a half-drunk bottle of wine, and an opened notebook. Glancing with pleasure at some half-written poems, the young man closes his homemade notebook and, raising the lid of the table, takes from the drawer several five-ruble notes. He places the notebook in the drawer and closes the lid. The poems will have to wait for tomorrow. Holding his shoes in his hands, he carefully opens the door to the dark hallway. Fumblingly, without turning on the light, he goes past the Amimov's door and carefully places the key in the lock of the door leading out, out of the apartment, to freedom…

«Eduard, where are you going?» Somehow, Celia Yakovlyevna, having heard the metallic sound of the key in the lock, or simply intuitively sensed that her son-in-law was escaping, has come out of her room and is now standing, having turned on the light in the entrance-hall, in her classical pose Number Two. One hand rests on her hip, the other — complete with the diminishing cigarette — by her mouth, her gray, slightly longer than waist-length hair loose, her well-bred face angrily turned toward her escaping son-in-law. The Russian son-in-law of her younger daughter.

«Are you going out to see Gena again, Eduard? Don't deny it — I know it. Don't forget that you promised that today you'd finish the pants for Tsintsipyer. If you get together with that Gena, you'll just… wander around…»

Celia Yakovlyevna Rubinshtein is an educated woman. It is awkward for her to say to a Russian young man, who is living with her daughter, that if he meets up with Gena, he will once again get drunk as a pig, and perhaps, like they did last time, his friends will have to carry him home.

«Look, Celia Yakovlyevna… I'm just going down for some thread… then straight back,» lies the shorthaired, somewhat puffy-looking poet, embarrassedly putting his shoes on the floor. He slips into his shoes and makes for the door, into the long corridor, bordered on both sides by dining tables, electric ranges and kerosene stoves. The fenced-off compartment with the kitchen and toilet — the priority for all the families who still live in this old building, number nineteen, Tevelyev Square — the corridor serves as a kitchen and the toilet is a communal one. Having passed through the entire row of tables, and inhaled, one after another, the smells of dozens of future lunches, the poet reaches the far end of the and heads down the stairs, taking them three at at a time. «Don't forget about Tsintsiper!» The pointless reminder from Celia Yakovlyevna reaches him. The poet smiles. What a name God gave this man! Tsin-tsi-per! The Devil knows what it is, but it isn't a name. Those two whole «ts»es, plus the completely obscene sound, «iiper»!

Genochka is waiting for the poet by the exit at the path to the Seminary District. There's a suitcase in Genochka's hand. «How much money have you got?» asks the Magnificent One, in place of a greeting. «Fifteen rubles.»

«Let's go, quick, or I'll have to wait in line.» Gennadii and the Poet walk hurriedly down through the Seminary Quarter, and, reaching the first corner, turn left toward the pawnshop.

The shadows on the street are heavy, dark blue. The sun is yellow as a rich, concentrated film of dyed butter. Without even taking your eyes from the asphalt, you can tell that it's August in Kharkov.

Even while they're several dozen meters away from the massive, fortress-like old brick building, the sharp, strong smell of mothballs reaches the two friends. For a hundred years, mothballs have been the foundation of this district, and it seems that even the old white acacias in this part of the street smell of mothballs. Hurrying along, the two friends go up the steps into a hall. The hall is high, roomy and cold, like the interior of a temple. Squeezing in among the old men and women, they get on one of the lines leading to the pawnbroker's window. The old men and women stare in surprise at the youngsters. It's unusual to see youngsters at a pawnshop in Kharkov. The poet, however, has already been to a pawnshop dozens of times. With Genochka.

«What have you got?» the poet asks his friend.

«My mother and father's plastic raincoats, a suit of my father's, and a couple of gold watches.» lists Genochka, smiling. His is a unique smile: malicious and precise.

«You're for it, Gennadii Sergeevich!»

«It's not your problem, Eduard Venyaminovich!» parries Genochka. But, obviously determined that his friend be subjected to a commentary, he adds, «They went off on vacation. For a month. And left me with just 200 rubles. I told them that wasn't going to be enough. And now look what happens; they must pay for wronging their only son.»

Genochka goes to the pawnbroker often, with his things and his parents'. He discovered this method of getting money before he met the poet Eduard. He pawns all of his father's things. His papa, Sergei Sergeevich, loves his handsome, stocky, blue-eyed son. Though Papa worries about his son's complete indifference to all human affairs except the quest for adventures and going to restaurants, and worries above all that now that Genadii is 21, worse things than pawnbrokers will befall him. A bad marriage, for example. It's Papa, not Genochka, who pays alimony to Genadii's former wife, and their son — his grandson. Papa Sergei Sergeevich is the director of the «Crystal,» the finest restaurant in Kharkov, and of the restaurant trust of the same name, handling many other «trading points.»

Genochka, not troubling himself about the things in the suitcase, pushes it through the welcoming slot in the window-cage and impatiently pounds on the patterned ceramic tiles of the floor with the heel of his shoe. They know young Ocharenko quite well in this pawnshop, and the transaction takes very little time. Ten minutes later the friends are already heading down the street, which smells of acacia and mothballs. Genochka has already contentedly placed notes worth sixty rubles in his black leather wallet. And, in another compartment, the pawn ticket. With revulsion.

«Well, where shall we go?»

«Deep South», v.2 n.1 (Autumn, 1996)

They're climbing over the stone wall which separates Taras Grigoryevich Shevchenko Park from the Kharkov Zoo. Naturally, they could simply buy tickets — for just one ruble twenty kopeks apiece — but the youths consider it a point of honor not to pay to enter «their» territory. The Zoo is a traditional playground for Ed and Genka, as for all the other members of the «SS»: the painter, Vagrich Bakhchanyan; «The Frenchman,» Paul Shemmetov; «Fritz» Viktorushka; and Fima, nicknamed «Dog.» Every member of the «SS» is in some way out of the ordinary. You couldn't call the «SS» a typical group of young people…

In Kharkov the August sun is pitiless. Nonetheless the two young men are wearing suits of the «dandy» style, introduced by Genadii and formerly championed by members of the foundry-workers' guild, and nowadays by the poet, Ed. Usually, once they've made it through the broken glass atop the stone wall, the kids jump to earth among the jungles of the Zoo, weaving through gigantic tussocks of steppe-grass and burdock, nut-trees and other August exuberances, then descending into the ravine by a little path which only they know, passing by an old oak which grows at the bottom of the ravine, and coming up out of the ravine right next to the «Tavern.» Its ancient sides, having once been covered with paint which started out as a reddish yellow, lean against each other. The young men's shoes are covered with the pollens exuberantly packed in several years'-worth of Ukrainian grasses — the heavily fertilized, crude, mighty Ukrainian grasses of the field across the way. Genadii is holding a package of bottles. Vodka. In the «Tavern,» they don't officially sell spirits.

Climbing up the path after his friend, Ed wipes his face with a handkerchief. From time to time they overtake a thick cloud of midges, which try to draw as many milligrams of blood as they can from their quickly-moving prey. Gena and Ed constantly wave their arms, or the cigarettes they're smoking, to repel the raids. Dripping sweat but unperturbed, they take the path to the summit and go on, along a narrow path between carefully-planted flowers, to the front of the «Tavern.» As if greeting their arrival, from the depths of the Zoo sounds the roar of a tiger.

«Zhul'bars,» states the poet.

«Sultan.» disagrees Gena.

On the open veranda of the «Tavern,» all by herself, doing something with the chairs, is «Auntie» Dusya. A big, strong woman in her thirties, with a red Bulgarian face, but still «Auntie.» «Hey, look vat showed up! Genochka showed up!» she exclaims joyfully. And why wouldn't she be glad? The dandy, Genochka, gives her more in tips than she gets in a week of serving eggs, sausage with peas, or chicken to visitors to the Zoo.

«If you please, Dusya, put this in the freezer!» says Genka, imitating his father, a former Colonel in the KGB and the Director of a Trust. Like his father, Genka addresses everyone with the formal pronoun. This is his own idea of chic. And Genka doesn't swear, which distinguishes him from Ed's many other friends, who curse non-stop.

«I am certain you have met Eduard Limonov, Dusya…?» Genka stares, with a certain patronizing irony, at Ed.

«Sure, you've had your friend here with you, Genochka…»

«Certainly, Dusya. But since then he's changed his name. Please take note: 'Eduard Limonov.'»

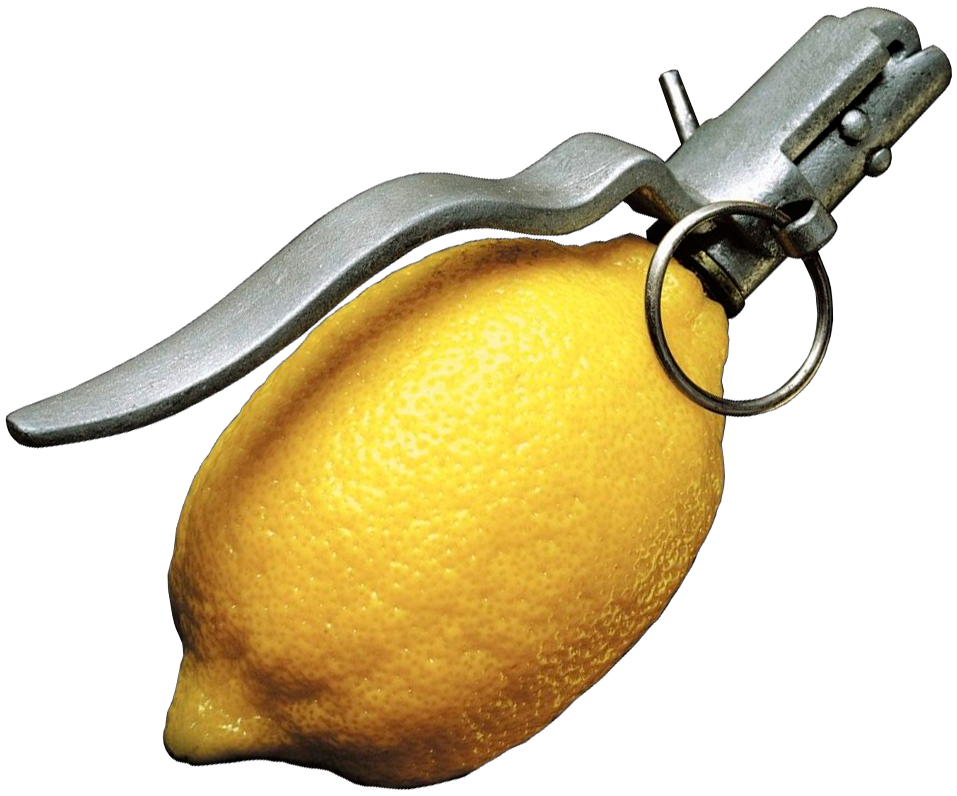

Eduard didn't change his last name, Savyenko. It's just that the «SS» and some other friends — Lyonka Ivanov, the poet Motrich, Tolya Melekhov, were sitting with Ed and Ann in their room, playing, out of sheer boredom, a sort of literary game, and they decided they would live in turn-of-the-century Kharkov and be poets and symbolist painters. And Vagrich Bakhchanyan made a rule that they all had to think up appropriate last names for themselves. Lyonka Ivanov decided to call himself Blanket. Melekhov became Breadman. And Bakhchanyan decided that Ed would be called Limonov. The game ended, they all went home, but the next day, while introducing Ed to a painter-friend from the newspaper «Leninist ____,» at the Automatic, Bakhchanyan referred to him as «Limonov.» And has called him that ever since. And it turned out that Genka really liked the nickname. All the young «Decadents» in the Automatic now call him Ed Limonov. The nickname stuck, and now even Ed himself doesn't call himself Eduard Savyenko much anymore. He has remained «Limonov.» Nobody calls Lyonka Ivanov «Blanket» anymore; nobody calls Melekhov»Breadman» any more; but Ed remains «Limonov.» Besides, for reasons even he doesn't understand, Ed himself likes «Limonov.» His real name, the very common, ordinary Ukrainian family-name, «Savyenko,» always depressed him. So let it stay «Limonov.»

The two young men are sitting at a table on the veranda, so that they can look out at the pond, and the swans and ducks swimming around on it. The «Tavern» is definitely the most picturesque restaurant in Kharkov, which is why Genka chose it as his headquarters. From the pond wafts the smell of muddy water. Two workers are lazily pulling a hose and just as lazily starting to sprinkle the heavy flowers.

«Well, what shall we have to go with our vodka, Comrade Limonov?» Genka takes off his jacket and drapes it over the back of the chair. He rolls up the sleeves of his immaculate white shirt and loosens the knot of his tie.

«Maybe some chicken?» Uncertainty can be heard in the poet's voice. He's gotten used to deferring to the more elegant, experienced and self-assured Genka on this sort of question.

«Dusya, what's good today?» Genka turns to «Auntie» Dusya, who has once again come up on the veranda.

«Oh, Genochka… it's still so early; how…» Dusya twists her frace into a pitiful frown. «The cook still isn't here; we only open at noon. I could get you a little snack, and, if you want, I could make eggs with sausage. When the cook gets here, he can make you Chicken Kiev…» Suddenly, a peacock cries out, long and loudly. As if at this signal, the whole Zoo begins to cry, roar and howl.

«Well, what do you think, Ed? Should we have some eggs with sausage?»

«Let's.»

«Dusya, make us some fried eggs with sausage. Six eggs each. With salt, but without lard — the way I like them. Bring them in the frying pan. And more vegetables, please — tomatoes, cucumbers…»

«Do you want your cucumbers pickled, boys?»

«Of course, Dusya, pickled. And a couple of bottles of cold lemonade. To wash them down with.»

«I'll pour you a little decanter of vodka, shall I?» Dusya glances at Genadii's face.

«No thank you. It would be warm. Bring us two wineglasses and put a bottle on ice, please, Dusya.»

The waitress leaves the veranda.

«Wonderful — eh, Ed?» Gena's fond gaze is directed toward the pond. Directly across the pond is the peacocks' aviary. Far away , among the cages, looms the huge bulk of an elephant. A draft suddenly wafts to the veranda the smell of dung and the nauseous smell of some musky beast. «Magnificent!» — And Gennadii's handsome face beams with tranquil delight. This is what he wants from life: a beautiful view, cold vodka, chatting with a friend. Even women are second-rate to Genadii. It's been a year since the beautiful Nonna, whom everybody thought he loved, appeared in his life, but even Nonna couldn't drag him away from his drinking sprees in the company of the «SS,» from his trips to a restaurant called the Monte-Carlo, from strolling down Sumskii Street with Ed, from the pleasures of wasting time. Ed Limonov looks with pleasure at his strange friend. Genka seems to have absolutely no ambition. He himself has admitted more than once that he doesn't want to be a poet, like Motrich and Ed, or a painter, like Bakhchanyan. «You'll paint and write poems; I'll bask in your success!»laughs Genka. Celia Yakovlyevna and Anna consider Genadii to be Ed's evil genius — they think he makes Ed squander money on drink, and takes him away from Anna. But this view of theirs is explained, actually, by jealousy. It's true, of course, that now and then Ed spends, with Genka, the money they've made sewing pants. Not often. But he doesn't go out drinking with Genka all the time. In any case, the miserly sums — ten, twenty rubles — he spends with Genka don't compare to the amounts squandered by Genka. And that phrase, «squandered on drink» somehow doesn't capture the Magnificent Genadii Sergeevich's style. The last time they went carousing at the Monte-Carlo — an out-of-town restaurant in Pesochin, watering hole for the high officials and KGB elite of Kharkov — Genka went first in one taxi, showing the way, and Ed followed in another taxi, and behind him came another taxi, empty, which Genka hired solely for the style of it, to make up a a cavalcade. In his youth, Sergei Sergeevich had been a regular at the Monte-Carlo — until his stomach ulcer. Gennadii inherited the place from his father. The staff knows Genadii Sergeevich well, and always gives him the best table. Until he met Genka, Ed had only read of «best tables» in books. At the Monte-Carlo, the chickens wander around right outside the window of the best table, and you can pick the one you want and they'll make chicken tabak from it. The paradox of the Monte-Carlo consists of the fact that the truck drivers eat in the big room, right next to a big highway. But at the best tables, it's the good life…

Auntie Dusya brings them their snacks, vodka, lemonade and, for each of them, a sizzling-hot frying pan full of fried eggs. Genka gazes with pleasure at the heavily-laden table. With one hand he raises the wine-glass of vodka, and with the other his glass of lemonade. «Come on, Ed!— Let's drink to this magnificent August day, and to the animals of our beloved Zoo!»

«Right!» agrees Ed, and they gulp down the burning vodka. And instantly start drinking the lemonade. And grab the pickled cucumbers and eat the fried eggs, burning themselves…

* * *

«Well, Ed, did you get a good scolding from Celia Yakovlyevna yesterday?» Genka has decided to take a break for a smoke, disengaging himself for the purpose from what's left of his eggs.

«I swear to God, I'm fucked if I can remember!» laughs the poet. «I remember getting out of a taxi, and grabbing the doorknob, and then… it all goes blank, I can't remember a thing. What time was it, anyway? Two o'clock?»

«What do you mean, two? It was still early. You passed out early last night. But Fima and I carried on drinking at the airport.

«No way I passed out.» The poet is offended. «I hadn't slept at all the night before, I was writing til dawn. Of course you're going to be tired after a whole night without sleep. You yourself threw up yesterday.»

«I throw up a lot.» agrees Gyenka calmly. «That's how the Romans did it. They'd throw up, then come back and drink some more.»

«That Celia Yakovlyevna caught me right at the door. 'And where are you going,' she says, 'Eduard?'»

«And what did you say to her, Eduard Venyaminovich?»

«Out for some thread, Celia Yakovlyevna, I'm going to the store.' With my shoes in my hands. I wanted to get out without being heard.»

«For some thread!» guffaws Genka. «Limonov went out to buy some thread!»

«Naturally Celia didn't believe me. But how is an intellectual woman going to argue with her Russian son-in-law? 'Then how come you've got your shoes in your hand, you drunk, if you're going for some thread? It's not a criminal activity, going for thread…'»

«She'd be ashamed to catch you in a lie. That's what comes of culture and education. A Russian mother-in-law would storm through the whole building, tear your sleeve off, dragging you back inside. It's a good thing you're living with a Jewish family… and Anna?»

«Yesterday Anna slept — and snored. She just opened her eyes and said, 'You got drunk with Genka again, you damned alcoholic!' and went back to sleep. And today I slept, once she went out.»

«You need to get Anna some kind of gift.» Genka frowns. «Ed, heading toward us are the first representatives of the goat-herd, who have already completed their morning excursion to the Zoo.»

A family is coming to the «Tavern.» Two children — boys of around ten — dressed, in spite of the heat, in blue wool thermal pants. The pants are too long; the cuffs, dragging on the ground, are gray with dust. The mother is powerfully built, surprisingly old for a mother with children of this age. Her hands and feet stick out awkwardly from her too-tight, too-short, white-and-blue polka-dotted dress. The father — who undoubtedly works in one of the many factories in Kharkov — is wearing a fake-silk yellow shirt and black trousers, sandals over bare feet, and carries in his hand a string bag. and in it something covered with torn-up and, for some reason, wet newspaper.

The morose children are the first up the steps. The mother after them. Having helped them climb onto the veranda, the father puts his foot on the first step. Genka stands up and sraightening his tie, assumes a stern look: «Comrades, comrades, entry prohibited! The restaurant is closed to the public today. Today is the All-Soviet-Union Convention of Bengal-Tiger trainers. Entry restricted to those with letters of invitation!»

The family leaves silently and submissively, dragging their string bag behind them. Ed even begins to pity the goat-herd family. «Why'd you do that to them?» he asks his friend. «Hell, they'd've drunk their lemonade, taken some sandwiches, and gone…»

«There's always noise from the goat-herd, Ed. Did you direct your attention to the children? Like little old men. Can you imagine how they would have gobbled, chomped?»

«You can't get rid of all of them… Now somebody else will show up.»

«Dusya, please place on all the tables on our side of the restaurant a «Reserved» sign.»

«Oh, Genochka, we don't have any signs like that!» whines Dusya. From beneath her feet, a big green grasshopper suddenly leaps, landing on the next table. This is the countryside; what do they know about signs? There's not even a toilet; visitors run to the ravine.

«In that case, write 'Reserved' on some pieces of paper, and put them on each table. Of course, your labor will be compensated.»

Dusya goes off to obey her orders. Her obedience is explained not only by the fact that Genka passes her a five-ruble or ten-ruble note as she leaves, but by the fact that the little Zoo restaurant belongs to the restaurant network of his Papa, Sergei Sergeevich, and in this network Papa is Tsar, Papa is God. True, Papa has sternly forbidden Gennadii to abuse his official position to get better treatment, but the power-hungry Genka can't resist the temptation to «abuse» it. Power — that's what Genka loves, Ed suddenly realizes. Power is Genka's ambition. Genka wants to brandish enormous power.

«Genka, why don't you join the Party and become an important man — say, District Administrator?»

«Are you kidding, Ed? That's so fucking depressing — making a career as a communist. It's bad enough that it ruined most of my dad's life — crawling on his knees.»

Even the fact that Genya swore testifies to his aversion to a Communist career. Genka is indifferent to ideology, Genka has no political views. What Genka wants from life is the «high»: pleasure, adventure, romance. And what kind of «high» is there in wearing a hole in your trousers sitting at Party meetings? Genka's favorite film is «The Adventurers» with Alain Delon and Lena Ventura in starring roles. That's what Genka loves — treasure-hunting, gunfights, expensive restaurants, crystal, cognac, candlelight, champagne… Ed remembers Genka's dilated pupils after the film. They watched «The Adventurers» twice — Genka, Nonna, as beautiful as Genka, and Ed. Genka is as handsome as Alain Delon, «The Beautiful One,» Bakhchanyan calls him. He's blond, six feet tall, light-blue eyes, a straight nose, a noble bearing. After «The Adventurers,» they drank and wandered around for a few days, and were arrested one night on the runway-area of the Kharkov Airport while trying to get into a jet transport. What they wanted on the jet will remain an insoluble mystery, but it is worth noting that «The Adventurers» begins with Alain Delon flying through the Arc de Triomphe.

«Let's do it, Ed!»

«Let's do it.» Ed looks fondly at his friend.

«Deep South», v.2 n.1 (Autumn, 1996)

«They're drinking, the scoundrels!»

Anna Moiseevna has appeared at the very moment when Dusya had refilled the young men's wineglasses. She is standing on the grass by the veranda, her bright eyes angry. Her robust body is covered by a crepe-de-chine dress. There are green, black and white flowers on Anna's body. She has a purse in her hand. Her graying hair is tied back in a tight chignon. Her turned-up nose gives her face a pert look.

«Ganna Miseyevna!» The idlers call out amiably. «Come over here and have some chicken kiev with us!»

«Scoundrels! Aren't you ashamed! Drinking vodka since early in the morning!» scolds Anna, but she goes around the edge of the veranda and up the staircase. A few representatives of the Proletariat, who have forced their way onto the veranda, stare inquisitively at the scene.

«You scoundrel! Deceiving Celia Yakovlevna, a poor Jewish woman, yet again! 'He went for some thread!' The simplehearted Celia Yakovlevna, child of another era — the angel who married my father… Celia Yakovlevna doesn't know what it is to lie! She trustingly believed that absurdity! 'For some thread, he went'!

«Fine — hit me! Give me a slap in the face!» The poet melodramatically turns his profile to his girlfriend and offers his cheek.

Gennadii Sergeevich becomes elegantly cordial.

«Pardon us, Ganna Moisyevna, for the love of God, and be kind enough to share this humble meal with us!» Genka takes Anna's hand and kisses it. Then, without releasing her hand, with his free hand he shifts the table and eases Anna into place at the table. Though she is still angry, she sits down.

«Dusya — please, set a place for Anna Moiseyevna… Anna Moiseyevna, it's my fault that your husband is here. Finding myself feeling somewhat lonely and depressed this morning, I deceitfully lured Ed away from his family, heedlessly seeking only personal and egotistical self-satisfaction…»

«The poor Jewish woman…» Anna Moiseyevna starts up her usual dramatic monologue, but provokes no reaction on the faces of Genka or the poet… «I ran right home… not a crumb in the house… 'Eduard went off to get some thread,' Mama announced, bewildered… 'He went off at nine o'clock, Mama!' I said, 'It's eleven o'clock — he went off drinking!' 'No… maybe he'll come back?' timidly suggested Celia Yakovlyevna, still believing in you…» Anna stared angrily at the poet. He bowed his head humbly, and Genka gestured to him with his eyes and his hands, «Just put up with it. Let her talk.»

«You didn't even leave the poor Jewish woman a ruble for food, you scoundrel!» Anna continues, «Meanwhile, we've spent all of her pension. I don't have any money — you know perfectly well I don't get anything in advance… after the account showed a gigantic overdraft, Gennadii» — Anna appeals to Genka. Genka nods sympathetically. «There was some hope that the young scoundrel would finish Tsintsiper's pants today and get ten rubles for them, and Celia Yakovlyevna could go down to Blagovyeshchenskii market and get some food… But the young scoundrel ran off…»

«Ganna Miseyevna,» says Genka quickly, while Anna gathers her strength for the next part of the monologue, «Be be good enough to accept from me a humble offering» — he takes a tenner from his wallet and pushes it toward Anna.

«We don't need your money, Gennadii Sergeyevich,» proudly declares Anna, who nonetheless looks at the tenner with some interest.

«Take it, Ganna Miseyevna! After all, it was I who took Ed out into the countryside, away from Tsintsiper's pants! It follows that I should pay the forfeit.»

«What?» Anna Moiseyevna stares questioningly at the poet. «Well, I'll take it… After all, we have nothing. Not so much as a crumb in the house.»

«Don't you dare…» spits out the poet. He curses himself for neglecting to leave Celia Yakovlyevna at least five out of the fifteen rubles left. Now Anna has the right to lecture him on morality and call him a young scoundrel. Normally Anna's a little scared of her poet, although she's six years older than he is. And weighs perhaps twice as much as the poet.

«Take it! You'll use it somehow or other!» With the help of an agile motion, the tenner ends up in Anna Moiseyevna's hand, and, from there, disappears into her purse.

«Have a drink, Anna Moiseyevna, a little vodka!» Genka himself pours Anna a glass, out of the bottle of Stolichnaya Dusya left with them the last time. «Have a drink and forget your cares!»

Anna can no longer resist; she smiles. «Scoundrel, you've been drinking for three days! And never once thought of the poor Jewish woman, wasting away in a newspaper kiosk. You could at least have taken the time to invite the Jewish woman to the restaurant.» Anna frowns and sips carefully at the vodka, unlike Genka and the poet.

«How in the world did you find us, Anna Moiseyevna?» Genka doesn't hide his pleasure and delight. He likes it when things happen. They've already gotten a bit bored, just the two of them making small talk; but now, voila, an unexpected appearance by Anna Moiseyevna.

«Genulik!» Anna looks at Genka with undisguised condescension. «Everybody knows that you and the young scoundrel are the only ones in the whole city with chocolate-colored suits with gold thread. First I went to the «Theater Club» and they told me they'd seen you this morning going down Sumsky street. I went to the «Lux,» and you weren't there. You weren't at the «Three Musketeers,» either. I ran around to all your hangouts, and at the «Automatic,» Mark told me that the young scoundrel, accompanied by you, Gennadii Sergeevich, had gone down into Shyevchenko Park. 'Where would people like you go, at this time of the year, when Nature is unbelievably flourishing, and the chesnuts are ripe, and the smell of flowers fills the air, and the world is making love endlessly?' I asked myself. Anna Moiseyevna sighs. Elaborate oratory is her weakness. Very often she inserts in her speech verses by living or deceased poets. «'People like Genulik and the young scoundrel can only go to the «Tavern,» and Dusya.' I said to myself, and came running here. Anna Moiseyevna has stopped, pleased with herself. «And here, if you please, I am. I'm not going to work!» She announces, after looking at her little watch.»What's the point!» she exclaims, staring defiantly at her «husband.» «I'll tell them I got sick.»

«You could be the Sherlock Holmes of the KGB, Anna Moiseyevna,» Genka says approvingly. «Yes indeed.»

«Lyonka Ivanov says Sherlock Holmes was a cocaine addict. That in between cases, he snorted cocaine.» observes the poet, after gulping some vodka.

«Lyonka Ivanov is a meshugginah,» Anna declares authoritatively. «They even kicked him out of the Army for being a meshugginah.»

«No way. Lyonka himself wanted to get out of the Army. When Lyonka came home on leave, already a sergeant, Viktorushka taught him what to do. The smartest thing is to pretend to be crazy. Viktor told Lyonka, and when Lyonka returned to his unit, he did exactly what Viktor suggested. At lunch time he went to the cafeteria, put a bowl of porridge on his head, stuck cutlets under his sergeant's epaulettes, and in this costume went running out of the dining hall… another time he went into the hall where the soldiers were watching a film and ripped the screen off the wall… but all just so he could get home; actually Lyonka's saner than me or Genka,» Ed ends his apologia for Ivanov.

«Ed, I think Anna's right; Lyonchik Ivanov really is crazy.» disagrees Genka. «Not dangerous, but pretty brainless. Have you noticed his expression?»

«Oh — then who's sane? Is Ganna Miseyevna sane?» Ed laughs scornfully.

«I tried to do away with myself once. But you, Ed — lots of times!» Anna almost shouts, leaping out of her chair. «It's true, I was classified as a Group One invalid by reason of craziness, but I was nineteen, and that son of a bitch, my first husband, had dumped me. When you were nineteen, you still believed in people!» Anna Moiseyevna, having lost her aggressive look, and aware of the goat heard, sits down.

«The hell with him, with Ivanov…» Genka says to them soothingly. Let's drink to you, Anna Moiseyevna, and to you, Eduard Venyaminovich, and to your union. May it be long and enduring!»

«To our cohabitation! To our unlicensed union!» laughs Anna. «To our situation! You know, Genulik, when the young scoundrel was already living with me in my room, but we were trying to make it look like we weren't living together… I would slam the door loudly at night, to deceive my poor Mama… so that when my Auntie Ginda suggested that we come visit her in a little room with two roommates, even that was an improvement in our material life. The intellectual Celia Yakovlyevna couldn't admit to the sister of her beloved deceased husband that her daughter was keeping in her room a boy six years younger than she, and sleeping with him. 'Akh, Ginda, we have such a situation at home!' that's all my Mama would say. How unlucky she's been in life. Papa Moise died of a heart attack, and her daughters have never found a decent life…»

«What? Her second daughter is married to the director of a factory. She lives in Kiev, right on the main street — on Kreshatik, in a big bourgeois apartment. People dream of a son-in-law like Teodor. The director of a factory…»

«My kid sister is in a good situation, __________[dazhe toshno],» agrees Anna Moiseyevna, taking a tidbit of cucumber, «but my niece, Styelka, is a whore. And she's sure to become an even bigger whore. Already she sleeps with any loser who comes along. Gyenulik, this long-legged Styekla keeps an eye out for every prick around, the kid had her first abortion at age 14! I only lost my virginity at 18…

Genka laughs. «Different times, different customs, Anna Moiseyevna!»

«'O, Lautrec, you will never reach the pedals!'» Anna suddenly recites. «'O Lautrec… __________________________________/'» Anna falls silent, having forgotten the next line, as usual.

«Whose is that?» Genka asks respectfully. He considers Anna an intelligent and well-educated woman.

«Miloslavskii. From his early poems.» mumbles Ed. «Yura poses, frenchifies, and nasalizes. He invokes the romantic underground life of the Parisian cafe and studio. Lautrec…»

«'Yet still I remembered how all these Magdalenes mended the cloak of the pockmarked Christ…» Glancing insolently at her «husband,» Anna once again recites Miloslavskii. And, of course, she can't remember the last lines. «Three Bandits with Aphrodite by the Fire,» she manages to force out, and then falls silent.

Anna's memory is stuffed with bits of poems, songs, which she heard some time, or clever phrases she read somewhere, from various philosophers and writers. From time to time Anna brings to light some fragment, line, verse or phrase, and inserts it in the appropriate part of her monologue. When they were just getting to know each other, in their youth on the outskirts of Kharkov, straight from the «Hammer and Sickle» shop section, Anna's erudition seemed the height of intellectual achievement. Now, Eduard, having become Limonov, laughs at Anna's «streams of consciousness.» He uses her singsong intonation, imitating the pompous Romanticism with which, it seems to him, Anna recites poetry:

Give me a blue-blue woman

I'll trace a blue line along her spine

And I'll marry that bright blue line…

Ah, I don't need no blue girls to marry

I'll howl with the cats on roofs so starry…

«Shut up, scoundrelly Savyenko!» cries Anna. «Don't torture my friend Burich's verses! You're not mature enough to understand them yet!»

«A bad poet,» rules Limonov remorselessly. «I, Genka, thought for a long time that Burich was a good poet, or at any rate an original one — and suddenly I happen to come across a book of poems by the Polish poet, Ruzhevich. And what do I see there, Genka?! Ah! What's it called?— Plagiarism! Especially when you consider that Burich and his wife are paid to translate Polish poets!»

«Burich is a great poet!» Anna's eyes rest, with nervous hatred, on her «husband.» «Especially because they publish so little of Vova Burich.»

«'Vova…'» snorts her «husband.» «They say he's already as bald as a kneecap. Vagrich saw him in Moscow, your Vovik. A big fat slob. A bourgeois of literature.

«That's not true! Burich is very handsome. Curly-haired, like an Apollo. Bakh was probably mistaken; it wasn't Burich…»

«What do you mean, mistaken… It was him — Apollo, your husband's friend — a genius from Simferopol…»

«They were all so talented, Genka. Don't listen to the young scoundrel. Talented and exceptionally intelligent. They knew everything. They read all the time. They were better educated than you…

«Talent has nothing to do with education.» Ed scowls.

Ed envies Anna's generation — her former husband, a television director; her husband's friends, who all moved to Moscow — the poet Burich, the film critic Myron Chernenko, the painter Brusilovskii. For Kharkov youth of Ed's age, for the bohemians and the decadents who got together several times a day at the «Automatic» to drink coffee, Moscow burns, as it did for Chekhov's three sisters, with a blinding, alluring light. Among Anna's contemporaries, the painter Brusilovskii is especially noteworthy. Vagrich Bakhchanyan speaks respectfully of Brusilovskii's work. Brusilovskii long ago started showing even in international exhibitions, and from time to time, reproductions of his works appear in Western publications. Anna's former husband is the least successful of them; he doesn't even live in Moscow, only Simferopol. Eduard very much wants to go to Moscow, so that he can join the previous generation — those about ten or fifteen years older. Join them, fight them, and hold tauntingly over Anna's head the name of her own Eduard Limonov.

The sun has suddenly peeked over the roof of the tavern, right above the table, and the wooden table, cleaned over and over, scratched, laid with tablecloth and snacks, nestling bottles of vodka and lemonade, the table is suddenly bathed in light. Very beautiful is their table, reader. A salad of red, blood-red Ukrainian tomatoes and tender green cucumbers, dripping with salted butter; the sun — many suns — refracted in the wineglasses and tumblers on the table.The dark burning hands of the poet, Anna's hands, her fingernails, as always coated with an unusual lilac polish, Gennadii's beautiful hand grasping the stem of a wineglass… the stone in Genka's cufflink, suddenly catching the sun, shines out a pure red light.

«Is that a real stone?» Anna takes Genka's hand. There is respect in her voice.

«Are you serious?» Genka laughs. «It's fake. But fashionable. I'd've pawned a real one long ago.»

«Oh Genchik… you're going to break Sergey Sergeevich's heart.»

«It's nothing, Anna. My Dad's got lots of money. And then too, he owes me something in this life…»

«Deep South», v.2 n.1 (Autumn, 1996)

Eduard met Anna Moiseyevna Rubinshtein in the Autumn of l964. Borka Churilov introduced them. Eduard was 21, and had just quit the «Hammer and Sickle» factory, where he had worked with Borka in the foundry for a whole year and a half. A short-haired, sunburned, _______ [mordatii] young worker, squinting to hide his extreme nearsightedness, looking for work, and his guardian angel, Borka, introduced him to the Poetry Shop, which needed a bookseller. In walked Anna Moiseyevna: beautiful, greyhaired at 27, scraping with her sharp metallic heels, inquisitively flashing her blue-violet eyes. And the bookselling job was instantly taken.

It would be simple to explain their liason by saying that the young worker needed a Mama. But, in this case, primitive Freudianism cannot offer any explanation or critique of so self-reliant and self-willed a personality as that of Eduard Savyenko. And Anna Moiseyevna, an unstable, eccentric, volcanic woman, would never have been able to be that sort of Mama. Therefore, instead of a Freudian, a socio-psychological explanation suggests itself. To wit: Eduard Savyenko needed a milieu. And the people among whom Anna Moiseyevna lived suited him. By the age of 21, he had been a thief, a burglar, a foundry-worker, a high-rise fitter, a stevedore, a wanderer through the Crimea, the Caucasus, and Asia, sometimes beginning poems,then throwing away poems; yet he had never found himself. He didn't know who he was.

At the foundry he was a good worker, and his portrait had appeared on the honor roll. He had six suits and three overcoats, and every Saturday he drank precisely eight hundred grams of cognac at the «Crystal» restaurant with his friends, young workers and girls. He was not, of course, acquainted with Genulik, son of the restaurant manager. The girls from the neighboring area, moulded from paraffin in the foundry forms, called our young hero «The Slave,» for his inexplicable persistence and diligence in the heavy, terrible three-shift work of the foundry floor. His partner on the shift, the fiftyish slob Uncle Seryozha, who looked like a crab, considered Eduard a good fellow, though too fond of work, and called him «Endik.» And then, one day,

«Endik,» to the utter surprise of Uncle Seryozha and the whole foundry team (he had already worked there _______________________) quit the division. He was bored. He'd had enough of it.

The main reason, which was not known by many people, and which has remained little-known (actually, every event, except the most obvious ones, has a real, secret reason) was that in the spring of 1964 Eduard met Mikhail Issarov, already known to the criminal investigation divisions of the countries of the Soviet Union for his brilliant credit fraud schemes. An affable little Jew, who had flunked out of the Gornii Institute, and fled from the Don Basin, where he had worked for a few years as a mine-director, to Kharkov. Besides this, he had also worked as the main organizer of gangs of con-men. Mishka appeared in Kharkov with his partner, the only remaining members of a group of arrestees. Mishka had family in Kharkov — his mother, father, and brother Yurka — noble toilers already known to us at the «Hammer and Sickle» Factory. Standing by the bars of the cell, Yurka introduced Ed to his brother-in-crime. Ed liked Mishka. Mishka was small and cheerful, wore a moustache, and lived the life of a millionaire. For example, he used to fly from the Don Basin to Moscow every week to get his hair cut.

Mishka had money. He needed two internal passports. For himself and his partner, Vitka. And our hero, remembering his criminal past, used his old connections to put Mishka in touch with his friends at the «Hammer and Sickle» dormitory. They «found» Mishka passports, 35 rubles each, stolen from other friends in the very same dormitory. Mishka stayed on in Kharkov and returned to credit scams. Every day, Mishka and Vitka left the Red Star Hotel on Sverdlov Street, which they shared with majors and captains, since it was a military hotel, and went out raiding the shops of Kharkov. With the stolen passports and certificates from their places of work, they «bought» on credit piles of gold watches, jewelry, expensive material for making suits and overcoats, and even televisions. All these blessings of civilization were acquired via swindle at less than one-quarter their price and resold on the black market. Mishka had invited Ed to dinner many times; one day, Ed, desiring to show his gratitude, introduced Mishka to the Asiatics from the Horse Market, who bought a good part of Mishka's goods. Another time, the inquisitive worker Savyenko, one week when he was on the third shift, helped the swindlers remove large quantities of jewelry, keeping watch while Mishka and Vitka worked.

Even law-abiding people get nervous. What, then, can one expect of criminals, whose work involves so much anxiety? Soon Mishka and Vitka began quarreling and arguing. And split up for good. There was a fight at the Red Star Hotel, and at the time of the fight, the buddies split up the cloth and jewelry, summoning the terribly carefully noble Yurka, and the far less scrupulous worker Eduard.

Several days later Mishka invited Ed to a restaurant and, at the end of the meal, over cognac and cigars, invited Ed, in the tone of a gangster from a Western film, to work with him. Tapping the ashes from his cigar, Mishka withdrew from his pocket a carelessly crumpled bundle of twenty-five ruble notes, paying Ed off and simultaneously suggesting for Ed the prospects in his «work» in Odessa, Kiev and Simferopol.

«And then, Ed, with all the loot (but we're going to specialize in jewelry, just jewelry, this time) we'll move on to the Caucasus and sell it all there. Here in Kharkov, we'd have to give the stuff away at half price to the Chuchmeks; there, we can sell it at full price. Well, Ed?»

Reader, when you are twenty-one and someone offers you money and travel, how can you resist? Eduard, whose prospects consisted of boring work in a hot foundry, agreed to join Mishka.

Mishka decided to go to Odessa at once. It would have been dangerous to stay in Kharkov, where Vitka and Mishka had been operating all summer. The occasion of the break between the partners, alas, was a genuinely dangerous occurrence in which our hero, as it happens, had a part. Mishka (he insisted that the head of the credit bureau of a big department store had realized the picture on his passport was fake, or maybe he just got nervous) ran out of the department store, knocking people down. After him ran Vitka and Eduard. But Mishka had left in the hands of the thieves' enemy his passport, with his photograph! Mishka wanted to get out of Kharkov in a hurry.

Eduard was delighted with the prospect of changing his life and said he was willing to leave that very day.

«No,» Mishka said suddenly, «Settle accounts with your work. Write a statement of resignation today and keep working for the next two weeks. At least one of us ought to have an authentic internal passport. With registration and all the stamps on it.

Eduard pouted, unsatisfied. «Listen to an older and more experienced comrade,» Mishka said. «Never do anything illegal, if it's possible to do it by legal means… I'm going on ahead to Odessa, but I won't be «working» there. In two weeks you'll meet up with me. As soon as it's set up, I'll send you a telegram with my address in Odessa… By the way, you don't happen to know a good tough kid who'd be willing to come along with me… I'll pay, of course. He doesn't have to know anything about our business. I need a bodyguard.»

Oh, Mishka Issarov had style! Eduard found him a bodyguard; the robust athlete Tolik Lysyenko traveled to Odessa with Mishka that same evening. Eduard gave notice at work and began waiting…

Two weeks went by, and the foundry boss tried for two hours to persuade the «Slave» not to leave; but running into Eduard's stony determination, gave up and signed the form. Eduard got his severance pay, but there was no telegram from Mishka. «He must've been lying to me…?» Eduard wondered sadly. «Just making fun of me…» «The Slave» wanted a new, wild life; his childhood dream of becoming a great criminal had been so close to coming true, and now…

Three weeks after Mishka's departure someone knocked on the door of the Savyenko apartment. Eduard opened it. The frightened and guilty-looking Tolik Lysyenko stood at the door. «Let's go. I have to talk to you, Ed!» They went out by some vacant land. Tolik kept looking around the whole time. sitting down on a pile of warm bricks, Tolik told him his Odessa story.

In the beginning everything was fine. Thanks to a bribe, Mishka and Tolik managed to get set up in the safest possible place: a KGB sanatorium! They played tennis, got some sun, swam… Then a former girlfriend, an actress, betrayed Mishka. She ran into Mishka by accident on Deribosovskii Street, saw and called out to him, and agreed to a date. When Mishka showed up for the date, they arrested him. It turned out that the actress, knowing there was a big hunt for him, had gone around asking about Mishka that spring… Oh, women… The actress had some kind of grudge against Mishka — he'd dumped her or something, way back…

True to his tradition of swindling with style, Mishka, whom they should have transferred to Donyetsk, the scene of his crimes, to be tried and judged, bought for himself and his two guards a first-class cell, and passed the time getting drunk with them. The agents had no objection, since Mishka's money would have gone to the State anyway — that is to say, to nobody.

After a month Eduard was restless. Despite an acquaintance of many years, and an entirely truthful explanation by Tolik, he wondered why Tolik had not been arrested with Mishka. He considered the possibility that Tolik had betrayed Mishka. People betray each other all the time, and everyone has a dark side. Or maybe Mishka decided he didn't need them involved in his business.

But Mishka had not deserted, and even Vitka had not betrayed them. Mishka even managed to hide his Kharkov period from the trashes. It was only for his «business» dealings in the Donets Basin that he got nine years penal servitude. The name of Mikhail Issarov, the first man to have robbed the Soviet State in the area of credit fraud, may be found in Soviet textbooks on criminology. As for our hero, he, as you see, had been, for the second time (the first being the day in 1962 when his mother had persuaded him to go with her to celebrate Aunt Katya's birthday, and Kostya Bondarenko, Yurka Bembel, and Slavka «The Suvorovian,» who had come to pick him up, couldn't find his building and went off on their errand without him) miraculously saved from prison.

«Deep South», v.2 n.1 (Autumn, 1996)

At any rate, Borka Churilov established his lifelong protege as bookseller. In store No. 41, which had branched off from The Poetry Shop. The boss, Liliya, was a mean little blonde, whom Anna christened «The Little Fascist.» She accepted «the little boy» willingly. Only «little girls» worked in the store. Liliya, Flora and «The Zombie» in a scraggly fur coat.

Every morning he came in on the trolley from the Saltovka district. Every morning he would pick up his stock and take it to the place where, having put it on a folding table, he would sell it. After completing the transfer of the books, he would begin arranging them on the stand. At first, while they were still explaining things to him, he set up his stand on Sumskii Street, right at the very doors of Store No. 41. Afterwards, he operated in the foyer of the Komsomolskii Theatre and at other crowded spots.

The bookseller's profession has some similarities to that of street-hawkers or snack-vendors. The bookseller recieves a paltry salary, but has the right to keep a certain percentage of the take. The outstanding bookseller in Kharkov, at the time Eduard Savyenko joined the profession, was the former railwayman Igor Iosifovich Kovalchuk, who had sold, at one time or another, for all the bookstores in the city. Of course, neither at the beginning of his career as a bookseller nor at its end could Eduard Savyenko compare in productivity with Igor Iosifovich. They hired Igor Iosifovich when they needed to fulfil their quota. They offered him higher salaries or bribed him. Because Igor Iosifovich could sell any book. Usually he set up his several tables in the center of Tevelyev Square, like an Asian vendor, crying out to the sky, about his books, hawking his wares in a hoarse voice: «Look! A history of the most terrible crimes in Antiquity! The battle between black and white magic!» It was difficult for passers-by to withstand these lures. There were always crowds gathered around Igor Iosifovich's stand. The «Story of the Greatest Crimes in Antiquity» might turn out to be simply a volume from the textbook, «Treasury of World Literature,» issued by the Academy of Sciences.

«Ed,» as Anna called him before the adoption of the last name, «Limonov,» was shy. He hunched timidly behind his book-covered display table. Sometimes there were two tables. Ed sat timidly and, for the most part, said nothing or smiled diffidently. Despite the straight-razor the bookseller often carried in his pocket, the bookseller of store No. 41 was not an agressive young man. Sometimes Liliya would send out, to reinforce him, «The Zombie» — a skinny being of the feminine variety, always wrapped in a shabby old fur coat. «The Zombie's» nose was always frozen, and its long tip was of a bluish color.

Eduard Savyenko didn't earn much money. To speak more precisely, he earned almost nothing. Yet the rapid pace of events managed, in October, November and December, to transform the half-criminal young worker into something else, something not quite clear — but at the very least, he entered, in those cold months, an entirely new social class. Imagine, reader, how difficult a process this is. Sometimes this sort of transformation requires several generations!

Every evening the bookseller hurried to get the stacks of books, and the tables, back to Store No. 41. Like a worker-bee hurrying back to the hive, like a bird to its nest, a jet to the airport. The bookseller hurried along — awaiting him was an appointment with the future, concealed in the alleys of Shevchenko Park, in the «automaticic snack-bar» on Sumskii Street, and in several Kharkov apartments. The future was hidden in the murky urban twilight, draped in rather old-fashioned clothes — symbolist, surrealist clothes. Though provincial, Kharkov, former capital of Ukraine, knew how to play cultural games.

There were many people around. Hundreds, at the very least. New, interesting people, unlike anyone else. In the little «storeroom» of Store No. 41 there were always lots of people sitting, avidly reading manuscripts. Poems, for the most part. The clean-shaven physicist Lyev, who had just returned from an expedition to Leningrad, brought back five or six examples of Brodskii's poem «Procession». An early poem, an imitation of Tsvetaeva, this poem lacked artistic integrity, but suited very well the socio-cultural stage which was occupied (better to say, at which will always be occupied) by Kharkov and the majority of the «Decadents,» who tramped along the triangle formed by Bookstore No. 41, The Poetry Shop, and the Automatic. So the poem enjoyed an unusual popularity. People stood in line to read Brodskii, from the time the bookstore opened to the time it closed. One of these readers was the poet Motrich.

Looking back and placing Motrich's greatness in historical perspective, it is necessary to note that at that time, Motrich was not the genius his worshippers considered him in 1964; he was not even known as a poet by many people. If there was a spark of genius in him, it was unnoticed. Yet Vladimir Motrich — as the past master again reminds us of his «Hammer and Sickle» factory (later Eduard Savyenko suddenly remember remembered, that Boris Churilov took him to the furnace, where the «real poet» Motrich still worked in l963) was, beyond any doubt, a POET. An original POET, since a poet is not merely a certain number of verses, but a soul, an aura, a taut field of passion, a radiant personality. But Motrich worked at it, oh yes…

One day… Ed the bookseller handed over the books to Director Liliya and she determined what he would make for the day. This operation was supposed to take place every evening, but both the bookseller and the director arranged,through laziness, to fix the books only weekly… alas, it came up 19 rubles short. In a rotten mood, Eduard came up out of the basement-level office to go down Sumskii Street to the stop where he would take the tram back to boring old Saltovka. But right at the last step the bookseller came face to face with a sort of moving wall, composed of the girls Mila and Vera and the poet Motrich. Snow was falling; Motrich's long skinny frame was encased in a remarkable black overcoat with a shawl-like collar. The Kharkov «Decadents» had already christened Motrich's overcoat the «badger-fur coat.» It all likelihood, even Motrich himself considered his coat to be badger-fur. At any rate, he often, and eagerly, declaimed the appropriate verses from Mandelshtam.

«Ed!» Motrich called out to the bookseller. He was secretly delighted. A smile was dying on the poet's Croatian face, a face with dark, hollow cheeks and a long hawk-nose with dark, coarse bristly whiskers, clearly visible in daylight, growing from the nostrils. «So it's you, Ed? You work here, with Liliya?»

«Yes,» acknowledged the poet, «It's me.»

«Great!» Motrich exulted, and the girls laughed melodiously.

«What're you doing, Ed? You busy?»

«I'm going home,» the poet announced gloomily. «I'm not doing anything.» He had already worked «with Liliya» for a week, and he had already noted enviously that in the evenings, a crowd would form, gathering either at the store or near it, and set off happily for the secret nocturnal Kharkov. Ed the Bookseller usually went home. One time Borka Churilov, he was on the first shift, took Ed to the «Automatic,» also called the «Machine-gun.» In the clear light of late afternoon the long, horribly contemporary self-service cafe stood snobs in high-collared overcoats and tight pants, drinking coffee from tiny little cups. There was even one with an umbrella-walking stick.

«You want to go have a drink with us?» asked Motrich, and then explained, «In honor of the first snow.»

«Sure,» agreed the bookseller, almost jumping for joy. Motrich was the first living poet he had ever met in his life. How could one refuse an invitation from one's first living poet to drink to the first snowfall? Mila took the bookseller by the hand, and the foursome went off down Sumskii Street, and the snow came down, and for some reason they were all smiling…

They drank coffee and port at the «Automatic.» The bookseller, indescribably honoured to form part of Motrich's entourage, was introduced to a number of snobs — and to a number of young people of another category: intentionally badly dressed and unhappy-looking. «Bohemian,» explained Motrich, noticing the astonished expression of the former steelworker, when a pale, greenish youth in a military greatcoat without belt or overcoat, and black boots that were falling apart, shuffled past them, leaving a damp trail behind him (undoubtedly his boots were leaking) and tossing out a few words in Motrich's metre.

«Kuchukov, a surrealist painter,» was Motrich's commentary. «His daddy's a militia colonel.» — and, seeing that a militia colonel did not make much of an impression on the bookseller, added, «But that's not even the most surprising thing, Ed. Yurka's an Ostyak, the last representative of a dying Siberian tribe. He swears that his ancestor is Kuchum Khan… the one who was defeated by Yermak Timofeevich…»

«The guy's probably lying,» thought the not very trusting bookseller, but he did not confide his thoughts to Motrich, maintaining his reserve. The other young men and women he met that night were also provided with absorbing capsule biographies by Motrich.

Having spent an hour in the «Automatic/Machine-Gun,» in which time Motrich had three «triples,» little cups of special-strength coffee made for him by «Auntie» Shura, they got a couple of bottles of port from the grocery store and, strolling down Sumskii Street, set out through Shevchyenko Park, already white with snow. The company amused itself at the expense of the round-faced Tolik Melekhov, who taught in the Philological Faculty of Kharkov University and kept watch by night in the boiler-room of a multi-story apartment building. Sitting down on a bench, Vera took off her mittens and with them brushed away the snow on the bench for a long time and with evident pleasure, and they stood to listen in the trampled snow in front of Motrich's bench. The poet's badger-fur coat was open. In one hand he held a bottle of port, and from time to time took a good gulp of it. Motrich recited poetry. Eagerly, the way starving people eat. Hardly stopping to take a breath, he read. As substantial things, rather than light, immaterial words, proceeded the verses from his Croatian throat. He read Mandelshtam and Brodskii's «Rat-Catcher»; he read his own verses:

And Jesus himself, like a horse-thief,

In a shirt of colored cotton…

The deep whisper (and especially disturbing, like a mutter, the «s» sound in the name «Jeessss-ussssss) of the living poet made all the hair on the bookseller's neck stand up for the first time in his life. Unmoving, hypnotized, mouths open, Mila and Vera leaned against each other, staring at Motrich. Having heard this poetry hundreds of times, perhaps…

«Recite 'The Wooden Man',» asked the student Melekhov. «OK, Volodya?»

No one had to twist Volodya's arm. Moving closer to the bookseller, his newest listener, Motrich recited the story about the wooden man. This wooden fellow…

Lived in a little garret, up

A hundred winding steps

And on each one found

Human sorrow…

The bookseller learned that the wooden man loved an unfortunate doll, who betrayed him, dumping him.

From the glass beads

His soul is covered with broken glass

The doll went to the pink puppet,

To her secret liason

And away from the heartless doll

Upstairs to his garret ran

The little wooden man

The wooden man…

Despite several serious criminal incidents, several factories in which he had had to work, and several complex and not entirely innocent adventures in the Crimea, Caucasus and Asia, the bookseller still did not understand the doll's nature, did not know that it was all in the way of things, that the world is like that, that the doll always goes out to a secret liason with the pink puppet. The Croatian, whose family God-knows-what wind had blown into Kharkov, convinced him, overcoming the bookseller's own experience. And Eduard Savenko believed, that the doll's nature is like that… That's her, strongly depicted. In an instant Ed Savenko, not yet even having become Limonov, understood what awaited him. Understood and forgot.

Gazing at the dark poet (Croatian bristles poking through the skin), the bookseller promised himself to become a poet. like Motrich — »To be like that» he stubbornly insisted. To have two girls sitting beside each other staring admiringly at him. To have the roundfaced student Melekhov smiling in admiration and delight and silently moving his lips, keeping time, perhaps, to the rhythm of the verses… his choice of profession was settled.

Until three a.m. Motrich stood with the bookseller at the trolley stop and recited verses to him. That snowy night at the end of l964 was the first time the bookseller heard the names of Khlebnikov and Khodasyevich. The name «Andrei Bely.» And perhaps a dozen no less distinguished names. The last tram took a long time running out to Saltovka,

Melekhov's fate was tragic. But it would hardly be reasonable to part the years and go into it now. The bookseller walked home. It took him almost two hours to make his way along the white streets of Kharkov to the Saltovka stop and, at last, to go up to his parents' flat and lie down on the sofa which served him as a bed. But even then he could not get to sleep…

«Deep South», v.2 n.2 (Winter, 1996)

The next day, Melekhov, in a fashionable plastic overcoat, which he made look awkward — his simple round face not harmonizing well with the futuristic product of the Riga atelier — walked into the muddy foyer of the «Komsomol» Theatre, where the Bookseller had set up his tables. He took from his case, which he had laid on its side, a time-yellowed book in a shredded paper cover, covered with tracings.

«There!» said Melekhov. «Let's start with this one. This forms the base, the foundation. Without this book the contemporary world will be impenetrable for you. If you don't understand it — don't worry. You don't have to grasp it all at once. If you want, I can then explain the unclear parts to you. You have to pay really careful attention with this book!» — And, having furnished the Bookseller with the adress of the boiler-room at which he worked, Melekhov walked off to his shift, carrying in one hand his sack stuffed with books and abstracts. Ed took a look at the book. Introduction to Psychoanalysis. S. Freud. With Preface by Professor Ermakov.

«Tolik Melekhov's a really good guy. Get to know him!» commented The Zombie, who had set up next to Ed. It was the end of the month, It was the end of the month, the bookstore was trying to fulfil the plan, so they'd sent The Zombie along to help the Bookseller. «And how well he knows books!» The Zombie enthusiastically wiped her always-moist eyelashes. «Oooo! Tolik's got a real library! But he's really poor. He assembled it book by book, out of sheer devotion. What a guy!» The Zombie even clicked her tongue. «How lucky Anka is! What a husband he'll be!» The Zombie very much wanted to get married herself, and although she was still only twenty, from time to time The Zombie lamented her fate, still unfastened by the bonds of wedlock. Meanwhile, she was seeing some Yurii, practicing for pregnancy and householding.

«Who's this Anka?» wondered the Bookseller, thinking, Isn't it that maybe-Jewish lady with the stiletto heels and eyes as sharp as her heels, to whom Borka Churilov introduced him in the «Poetry» store?

«Anka Volkova's the daughter of a very important man!» said the Zombie very significantly, and for some reason in a whisper, as if entrusting to a comrade an old secret. Her pale-blue face, like that of a chicken which has been dead for several days, shone with her particular sort of religious rapture. «Anka Volkova's the daughter of Volkov himself!» and The Zombie stared triumphantly at her workmate.

«But who's Volkov?» wondered the ex-foundry-worker.

«Are you kidding? You don't know who Volkov is?» The Zombie suddenly stood up behind the counter and firmly grabbed an adolescent hooligan by the hand. The Bookseller got up too, and together the two of them managed to get the stolen book out of the thief's spacious overcoat. Then, having given the would-be thief a slap on the head, The Zombie sighed.

«Volkov,» she said, «is the director of the Kharkov Meat-Fish Trust.»

«Meat-Fish Trust» made no impression whatever on the Bookseller. Secretary of OBKOM, General of the KGB — there were several titles which could impress him. But «Director of the the Meat-Fish Trust»?

«So is she pretty, this girl?»

«You mean you never saw her — Anka? She comes here often. She was in the store just yesterday. Wears glasses. Tall. Rimless glasses.»

The Bookseller recalled this girl. Glasses. Surprised pink cheeks. Nothing fantastic, maybe a certain assurance in her manner… But for all his erudition, Melekhov had a simple peasant face. Even after a year the Bookseller would say, «The face of an intellectual of the first generation.» But now he changed his definition: «A simple face — in fact, a peasant's face.»

Obviously the Bookseller's dreams of the grandeur of the «Meat-Fish Trust» and of the daughter of its director showed on his face, because The Zombie filled in more detail on Anka Volkov. «Anka's very spoiled, and a girl of character. She loves Melekhov, but still torments him a lot. See, Anka also studies Philology. That's how they met.»

The Bookseller looked at his watch and started piling his books in the sack. The Zombie didn't object, and joined in putting away the goods. It was a quarter to eight. Early. Liliya always asked them to stay in the foyer of the theatre at least til a quarter-hour after tickets for the eight-o'clock showing were sold. Director Liliay insisted that book-lovers always chose this showing. The Bookseller knew that, counting the group of hooligans who had chosen the foyer of the «Komsolol» for their headquarters, the guys who had arranged to meet their dates there among the cracked batteries, there wasn't a soul in the foyer of the theatre by eight o'clock. So what books were they going to sell? Out on the street it was snowing hard, and people had long since gone home from work.

«Anka and Tolik want to get married. Anka's Mama is on their side, but her father doesn't know about it. They're afraid to tell him that Tolik even exists. He probably won't agree to it. Melekhov has no father, but his mother's a yardworker. The father wanted to give his only daughter Anna to someone of his own circle…» — The Zombie babbled as usual and as usual put the books into the strong, durable sack, while the Bookseller, Ed, tightens the drawstring of the sack.

«They marry off their daughters, just like in bourgeois society,» grumbled the Bookseller. «Who's Anka anyway… what's it to her who Melekhov's father was… 'Yardworker-Mother' — Anka, with her glasses, will look just as much like the daughter of a yardworker!»

«And what's your father?» Asked The Zombie.

«A captain,» admits the Bookseller. In the past couple of years, he's grown indifferent to what rank his father holds. Before, he was embarrassed about his father-captain. Another time he would have lied, and said that his father was a colonel. Why would he have lied? Maybe in order that the effulgent radiance of a full regimental colonel might have shone its social light on him, Eduard.

«Captain of what?»

«God only knows of what now. I lived with my parents for so few years that I don't even know where he serves.» This answer was truthful. Captain Savyenko worked, in his time, in the NKVD/MVD. Where he works now, Eduard has no idea.

* * *

«Guys! They sent us to take you away!» The poet Vladimir Motrich appeared in the foyer of the theatre, in person, shaking the snow from his lordly fur coat. Behind him entered a tall, stooped youth with a fat, dark face and a shiny profile. The youth stared amusedly and condescendingly at the books, at The Zombie, and at Ed. From one of the batteries in another corner of the hall, the hooligans, who until this moment had been peacefully carving coarse words into the plaster with their knives, greeted Motrich. Motrich answered the hooligans with a haughty circling gesture, hand over his head. Of course, the hooligans didn't read Motrich's verses, but Motrich lived on Rimarskoy Street, which runs parallel to Sumskaya, right past the theatre; that is to say, he was local, and and the local hooligans knew him.

«Let me introduce you, Ed — this is the painter Misha Basov,» ceremoniously stepping aside in order to give the Bookseller the opportunity to see the youth with the shiny profile. By the attentive way in which he stood aside — the care, thoughtfulness, even — it could be seen that the shiny youth was his close friend, and that Motrich was proud of him. The youth stared unceremoniously at the Bookseller. It might not be fair to call his glance haughty. But an untroubled arrogance was in this glance. The Bookseller noticed that the youth somewhat resembled a portrait from the beginning of the century — possibly he looked like Aleksandr Blok, the only poet, besides Yesenin, whose work the Bookseller knew well. Borka Churilov, back when they worked together in the foundry shop, gave him, for his birthday, nine blue volumes of Blok. Borka, like Pygmalion, guided our young hero into life.

«You're a friend of Churilov's, right?» asked the shiny youth Basov, in place of a greeting. «And, if memory serves, you write verses?»

«Used to.» Answered the Bookseller, ashamed.

«And what, you gave it up?»

The Bookseller nodded.

«And you were right to do so» — said the Blok mouth in calm approval. «Nowadays everyone writes poems… But Motrich is our only real poet.» He cocluded with this gross flattery and stared at his friend the poet. who at that moment, having removed from his head his fur hat, was brushing the snow from it. The tiled, «marbled» floor of the foyer was covered with a layer of dirty slush, carried in from the street by hundreds of feet. In the slush stood Motrich's skinny trouser legs, ending in short Czech shoes; and further on, the skinny black trousers of of the youth Misha Basov, covered with mud and tucked into two formless homemade boots tied up with many lace-holes. Having noticed these boots, the Bookseller forgave the painter for his outrageous falshood — that no one but Motrich could write good poems. For all his gifts, the youth was poor. Poor and intelligent — this combination the Bookseller respected in people. A thief or a bandit shouldn't be poor, thought the Bookseller. But a man of the arts — that's another matter. The classic artist — the painter, the poet — should be poor. It's obligatory. Like Van Gogh, whose amazing letters have just been translated into Russian, together with reproductions of his work, in a large, heavy book like a family album. The Bookseller got the book from Liliya and read it from cover to cover. Poor like Yesenin, who was always short of money…

With one hand, Motrich took the folded-up chair , and with the other he took hold of a packet of books. The bookseller took grabbed three packets, the table and one packet, and the Zombie, happily relieved of burden, ran ahead, then stopped further up Sumskaya Street, revelling in the snow which had already been muddied and churned by thousands of walking feet.

«Deep South», v.2 n.2 (Winter, 1996)

At this point it is necessary to provide an elementary outline of the history and topography of Kharkov, so as to make it easier to follow our heroes' movements in time and space.

«A large Southern city,» as Bunin called it… located in Europe, in the northernmost part of the Ukranian Soviet Republic, a few hundred kilometres from the border of the Russian Soviet Republic. It was founded either at the end of the 16th century or at the beginning of the 17th, by wild Cossacks who had been causing a great deal of trouble in the huge area between the fiftieth parallel (on which sits precisely the fat dot of the city, if you look at a map) and the shores of the warm Black Sea itself.

After the Great Revolution, and right up to the year 1928, the city served as capital of Ukraine. In those ten years Kharkov managed to build several absurd architectural monuments, which would never have been built if Kharkov had not been the capital. In November l930 a Conference of Proletarian Writers was held in the city, in which took part, among others, Romain Rolland, Barbusse, and Louis Aragon. In this city was born Tatlin, celebrated author of the tower project of the International, as well as the second-greatest poet of the OBERIYU Group, Vvedenskii — not to mention that insignificant figure, Kosygin. A further point of Kharkov pride is the multitude of factories located on its outskirts. Kharkov is a gigantic industrial center, much like Detroit, for example, in the United States…

Sumskaya Street is the main artery of the city, but not because it is the longest, widest, or most fashionable. Its popularity as an ancient road, leading to the other Ukrainian city, Suma, is founded on the fact that it's central — located in the exact center of the Old City — and also on the fact that at its exact center are located the city's best-known restaurants, theatres, and administrative centers. Sumskaya Street begins at Tevelev Square and runs, climbing upwards, to Dzerzhinskii Square. And right there at No. 19 Tevelev Square Anna Moiseyevna Rubinshtein lives quite comfortably with her mother, Celia; and there, at the beginning of l965, our hero, the «Young Rascal» Eduard Savenko, moved in. From the windows of the Rubinshtein apartment on Tevelev Square can be seen the building formerly occupied by the Assembly of Nobles, the corner of Sumskaya on which is located the «Theatrical» restaurant, and the building of the Refrigeration Technical School.

On Dzerzhinskii Square are located the many-columned and many-floored barracks-yellow headquarters of the Party Regional Committee. The square, which is still the largest in Europe, accomodates other, no less remarkable but less massive architectural landmarks: the ochre-coloured Kharkov Hotel, which recalls the step-pyramids of the Aztecs; the University, a smaller version of Moscow State University; and finally, that marvel, «GOSPROM» — the prison-like constructivist headquarters of State Industries — a grotesque heap of glass and concrete.

Basically, our hero's life has taken place between Tevelev and Dzerzhinskii Squares. On Sumskaya Street, between the two squares, is located not only Store No. 41, but also the Theatrical Institute, with its beauties promenading down Sumskaya at lunchtime, and the fabulous «Mirror Stream,» an unremarkable little pond with a waterfall, immortalized nonetheless on dozens of postcards and in every tour-guide to Kharkov. (In the archives of our hero's Mama, Raisa Fyodorovna Savenko rests a photograph of Eduard, age ten, standing by the «Mirror Stream» in a sky-blue belted jacket and knickers.) Just behind the «Mirror Stream» and the Theatrical Institute is located, on the ground floor of a tall building, the famous «Automatic» — a snack bar which is Kharkov's «Cafe Rotunda,» «Cloiserie de Lilas» or «Cafe Flore.» More precisely, the Automat fulfils all the functions of all these famous cafes. (It was here that an interesting idea occurred to our author: was not the sudden flourishing of Kharkov's cultural life at this time related to the opening of the «Automatic» Snack Bar?) A few buildings on from the «Automatic,» directly opposite the towering monument in memory of the «Great Kobza-Player» Taras Schevchenko, is located the central supermarket, rather important in the history of Kharkov during this period. In this very store the heroes of our book purchased their wine and vodka. Up Sumskaya, behind the grocery store, is located a two-story building housing the combined editorial offices of «Leninist Zmin» and «Socialist Kharkov.»